It’s also worth noting that he began diving well before either Cousteau or Bridges first dipped their faces beneath the ocean. Stan’s contribution to the popularity and initial recognition of scuba diving is virtually unequaled. Indeed, he has survived longer than any other diving pioneers (except Hans & Lotte Hass) and continues to spark audiences with his graceful charm and quick wit. From a humble beginning as a blueberry farmer in coastal Maine, he was inspired to start one of the first pure diving operations in the Bahamas. Chafing at confinement to one locale, he indulged his passion for diving by teaching himself the art of motion picture photography and producing some of diving’s earliest films. His first documentary in 1954, Water World, set the hook in the young adventurer and he widely toured the U.S. personally narrating the show to astounded viewers.

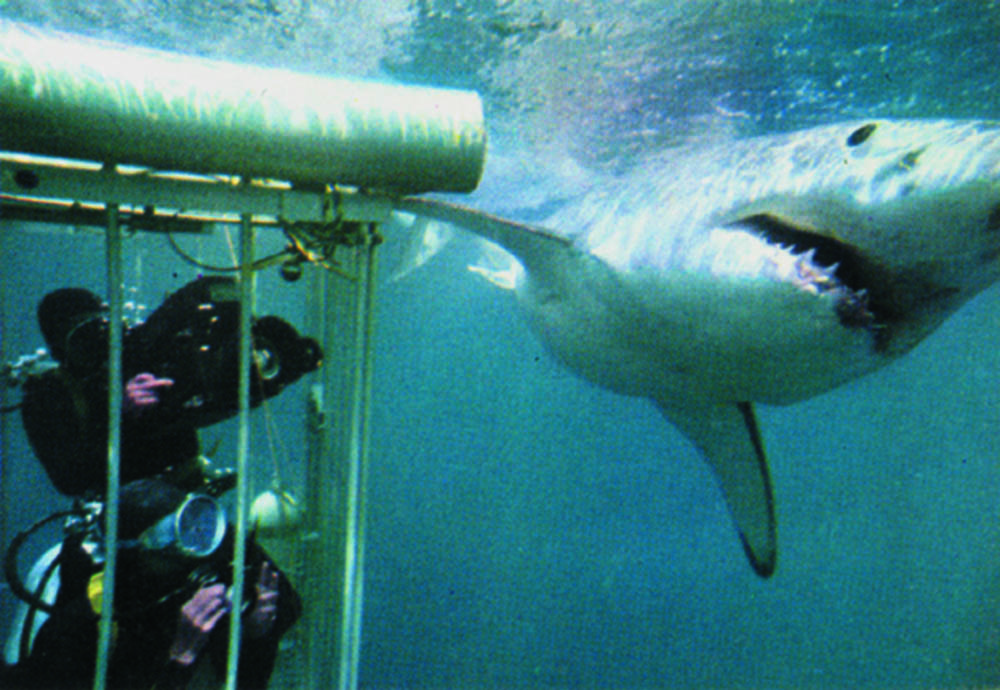

In 1959 Waterman participated in the first underwater archaeological expedition to Asia Minor to film a Bronze Age shipwreck. The resulting film, 3,000 Years Under the Sea, was a hit. His third effort in 1963, Man Looks to the Sea, won numerous awards including top honors at the United Kingdom International Film Festival. Following that success, he packed his entire family off with him to Polynesia for a year working on a film that became a National Geographic special. But one film was singularly most responsible for launching him into the consciousness of divers and the generally terrified viewing public: the astonishing epic Blue Water, White Death. Released in theaters in late 1970 after nearly two years in filming, the movie induced a primal gut reaction for most audiences that combined horror and fear with fascination. No one before had ever left the safety of cages to swim in open water with pelagic sharks. Waterman (with Peter Gimbel and Ron & Valerie Taylor) blew everyone away by leaving the cages to swim with hundreds of feeding sharks… at night. The film’s dramatic conclusion, featuring the first Great White shark footage ever presented, left an indelible impression on millions and firmly established Waterman’s reputation.

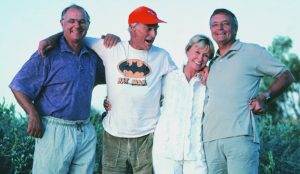

Following the popularity of the movie Jaws release in 1975, ABC latched on to Waterman to film an American Sportsman segment with author Peter Benchley. A year later Hollywood came calling to ask him to co-direct the underwater unit for The Deep. Over the years Stan has mentored and guided such current luminaries as Howard Hall, Marty Snyderman, and Bob Cranston while becoming a confidant and close personal friend of Benchley.They got together on the phone or in person almost weekly until Benchely passed away in earl 2006. Stan will be 84 by the time this book comes off the press and still keeps to a diving and speaking schedule that would daunt persons the age of his grandchildren. Don’t miss his excellent book of essays titled Sea Salt (also put out by New World Publications). This fascinating book recounts his career in a series of autobiographical chapters and others that simply relate stories of great diving adventures spanning seven decades.Stan and I have been friends for years. I stay over at his house in Maine and he visits mine. Lately I’ve been cruising over to his waterfront estate near Deer Island on beautiful Eggemoggin Reach. I anchor my motor yacht Encore in his snug harbor known as The Punch Bowl and we get together to share strong drink and tell stories. We’ve shared many stages over the years as well in Chicago, New York, and Boston and I always look forward to hanging out with a true American legend. There will never be a grander or more articulate spokesperson and ambassador for diving… or a better friend.

The Beginning of it All

.

Everyone has to start somewhere, what led you into diving originally?»While on Christmas holiday in Florida with my family in 1934 a lady who had just returned from Japan gave me a curiosity. The curiosity was a Japanese Ama diver’s mask. The Ama were the lady divers who breath-hold dived to harvest the seabeds around Japan. Their handcrafted full face masks preceded by many years the first appearance of face masks for divers in the Western World. I swam out with it along the breakwater in front of the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach, dove down, opened my eyes and was hooked for the rest of my life. I was 11 years old then. That was 73 years ago. It could have been yesterday. It is still fresh in my memory.

My father was a successful cigar manufacturer. Cigars were still king in the early 1930s when I was grown enough to relate with joy to the sea. My summers were divided with half going to my divorced mother at Rehoboth Beach, Del. The other half on the Maine coast at my father’s summer home. With ocean on three sides of the house, Maine was tidal pools, a first small sailboat for exploring the coast within sight of the house, and finally a tough Herreshoff sloop. I rigged a small outboard on the stern and sailed far out to the cod fishing grounds, often returning after dark. At Rehoboth Beach I body surfed every day with my gang and challenged the big waves in storm time. We were all as agile and unafraid as seals. So the sea was with me almost from the beginning.

You did time in the Navy?»During the war – that’s WWII – the one that would supposedly end all wars, I was stationed with a Naval Air Station in the Canal Zone. I trained as an aviation radioman gunner in SBD dive-bombers. There were California “ab” and “bug” divers in my squadron. We had acquired the new fins, masks and snorkels along with pole guns for spear fishing. The whole sport was so new that I actually corresponded with Owen Churchill. The year was 1943. He had invented the first fins for market in the U.S. They were called “frog feet”. With an order that he sent he pitched in a cork-handled knife in a wooden scabbard and asked for an opinion on its use. I can’t recall what I wrote to him. The knife was entirely ridiculous. But I made common cause with the California divers. We had a couple of motorcycles with sidecars and snuck off base to dive from isolated parts of the shore and spear anything that moved. We bartered the fish at the Ships Service. The local girls who worked there were delighted to take the fish home. We were delighted with free shakes and burgers.

After the war, a grateful government put me through college on the G.I. Bill of Rights. The gratitude was top-heavy on my side. I had never fired a shot in anger or faced an enemy during my four years in service. I had as fine a liberal arts education as one may have in this country. At Dartmouth I majored in English, focusing on Shakespeare. I studied with Robert Frost. I was a big enough athletic cheese (two mile and cross-country) to enjoy status. I started wooing my present wife of 58 years, a summer romance aided and abetted by her wonderful family taking me in. Both my mother and father had died early during the war. The only home I had when I emerged from college was the summer house in Maine. I wanted to live there. I married Susy two weeks after graduation. We took up residence in Maine, winterizing a part of the old house and I went to work as a blueberry farmer. Three economies dominate Maine (aside from tourism): lobstering, lumbering and blueberries.

What was your first scuba gear?»During the second year the Aqua-lung arrived in the U.S. Two Frenchmen, Rene Bussoz and Paul Arnold had the foresighted enterprise to buy the U.S. marketing rights for the Aqua- Lung from Cousteau for $10,000. I heard that Cousteau quickly realized his mistake and bought the company – called U.S. Divers – back, supposedly for a cool million dollars. I have always thought there was considerable hyperbole in that story. Whatever, I purchased my first Aqua-Lung from the first U.S. Divers Co. Cornelius made the only portable compressor available then and suitable for high-pressure breathing air. They made compressors for filling airplane tires. I acquired the 25th. The Aqua-Lung was probably the first in the state of Maine. Bill Barrada, of Skin Diver magazine, marketed a latex rubber, back or neck entry dry suit to be worn over heavy underwear for Maine waters. It was never dry. The crotch squeeze was excruciating; but I could take to the water with it. I charged $25 for my services, recovered scallop drags and moorings, unfouled propellers and for the grand sum of $125, threaded cables under the hull of a big work tug that had gone down in 70 feet of water within sight of our house. I even dove from the pontoon of a seaplane that flew me into a Maine lake to search for and recover a half dozen expensive rifles that had been lost when the hunters capsized their canoe. The adventure was supreme. My system was the only game in town. I eventually hooked up with a wholesaler in Ardmore, PA. who marketed Healthways line of equipment along with U.S. Divers scuba gear. I retailed a half doze full sets of equipment to adventurous friends in the area. None of them stayed with us but they all avoided death. In hindsight I realize how lucky that was.

One of your first forays into diving as a profession led you to take a converted Maine lobster boat to the Bahamas to run dive charters. What was the market then and who were your customers?»In 1953 I was inspired by Hans Hass and Cousteau to design a lobster boat hull especially for diving, helped to build it at a local boat yard and in 1954 took the 40-ft. Zingaro from Maine to Nassau. There I set up shop as the first liveaboard dive boat in business. Back then few people went to the Bahamas during the summer months.

Winter had the worst weather. Summer was the best time for diving. But the tourists did not know that. I hedged my bets, not being at all sure how this new enterprise would pan out, stored my boat each May up the New River in Fort Lauderdale and headed up to Maine to get the crew working on the blueberry land. In November, when the blueberry land was burned and put to bed for the winter, I would take the boat across the Gulf Stream, over the Little Bahama Banks and over The Tongue Of the Ocean to Nassau and start the diving season. We had good friends in Nassau, all divers and spearfishermen. They were my mentors in learning about navigating reefs.

Under Water Filming

How did you start in underwater filming?»The diving just barely broke even. But I had started shooting 16mm film with an early Fenjohn housing, then a Rebikoff housing, then my own plexiglass housings and commenced lecturing with my first film, Water World during my off-seasons at home. That led to another dimension and my own particular evolution in the business. Guests on my boat were the genesis of my extended reach beyond the Bahamas. I was invited to join expeditions in return for shooting and editing a 16mm documentary record. Zingaro circumscribed the range of my activities. I certainly could have dived the Bahamas for the rest of my life, but I wanted very much to see and dive in other parts of the world’s oceans. After three years of charter boating divers in the Bahamas I sold Zingaro and made my move. I planned to work with expeditions in the late spring and summer. The experiences would provide fresh material for lecturing during a season that generally ran from fall to April. My first economically viable season was 1959. An agent had picked up my act. For the princely fee of $125 per show I commenced a film lecture tour. Remember, television had not yet appeared on the scene. So called “Armchair Adventure” and – in New England – Athenium Lecture Series provided live entertainment for communities across the country. The speakers projected their films and narrated them live from the stage. I added music from a tape recorder that I cued from the podium. Three agents and three years later I was making $350 per date, doing block bookings across the U.S. and Canada plus the Hawaiian Islands. One exhausting, peak year I did 162 speaking dates.

I called it “Gum Shoeing In the Bible Belt”. I was on the road for three weeks to a month at a time, one-night stands in little towns and big cities as well. Big cities might have audiences of 2,000. Little towns – like Scarlet, Nabraska might have 350, almost the total population. For many small communities the lecture series were the only game in town. Most of the shows ran along the line of Norway: Land of Contrast, Exotic Hawaii, The Four Seasons of Scandinavia. My underwater shows were a total anomaly. I tried to make them entertaining and exciting. The hyperbole that attended shark and moray eel footage was outrageous but gratifying.

Sounds like you were away a lot?»Susy was practically a single mother. We had three children then, Gordy, Susy-dell and Gar in that order. Maine was too isolated for a family with an absent ather much of the time. The schools were rated the third worst in the country. I looked for a community that had good schools, a cultural matrix for Susy’s receptive mind and fine intelligence. I found it in Princeton, a university town with old friends to help us settle More important, Susy’s wonderful, supportive family lived only two and a half hours away in Pennsylvania. Important for me was a reliable major airport just an hour away. My old airport in Bangor, Maine was fogged in as often as not.

Family and a Career

Family and a Career

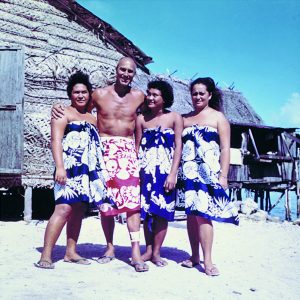

You have always tried to include your family in your adventures. What did they think when you hauled them off to Tahiti and Bora Bora for a year?»When I decided to take my family to French Polynesia for a whole year I had already been to Tahiti twice on contract, shooting underwater footage for other documentary filmmakers. So I had some friends and connections there to help me plan the real logistics of spending a year. Susy and I both wanted to have a family adventure together while the children were still young. Kenneth Graham wrote in The Wind In the Willows, “…for the days pass and never return.” We wanted that experience before the children were out of the nest and gone from us. They were then 10, 12, and 14. As they became full teenagers I used to take one with me each summer on whatever expedition I was documenting. One-on-one, we got to know one another. Those experiences forged a bond between Susy and me and the children that has never lost strength. The Tahiti year, as I call it, especially engendered a family esprit, the most valuable move we made in those formative years. So the children have never m ved away. All three live in Connecticut about two hours away. One or more call almost daily. We share all the major holidays. Gordy is 56 this year. Share with us some of the other destinations and films you chose to feature in your early career.»There were some fine adventures I lucked out with as professional contacts, new friends and acquaintances generated during my three years in the Bahamas made the new experiences available They were the grist for my lecture mill. Essentially I evolved from charter boating to working with others’ boats and facilities, expanding my range beyond the Bahamas. I hoped to produce a fresh lecture film each year, shooting in the summer and fall, then lecturing through winter and spring to amortize my costs and keep a roof over our heads. Thus my friendship with Drayton Cochran, a customer on Zingaro when I was still in the Bahamas, led to a trip through Europe on the rivers and canals from the North Sea to the Mediterranean in his 71-ft motor sailor, Little Vigilant. For my third cruise with Drayton I did the advance planning for a trip through the Aegean Islands, finally focusing on a rough archaeological survey of wrecks along the coast of Asia Minor. Ultimately we located a wreck off the Turkish coast opposite Rhodes that proved – at that time – to be the oldest wreck found. The clue had come from scraps of bronze found by Turkish sponge divers and heard about by an amateur underwater archaeologist, Peter Throckmorton, who came with us.

Didn’t you do some early work in South America as well?»Another expedition took me up the Amazon for the first attempt to capture and bring back alive the two species of fresh-water dolphins, Innia and Sotalia. The goals were achieved. The Niagara Falls Aquarium was the sponsor. We flew to Manaus, 1,000 miles up the Amazon, the last civilization, and from there went up river with a wood-burning steamboat – the last on the river – one barge for our hammocks and cuisine – another barge that we filled with water to transport the dolphins and Indian guides. It was an epic experience and totally successful. The dolphins were safely flown back to the States, introduced to three major aquaria and the first to be seen in the U.S.I have lost touch with them (that was about 45 years ago) but I believe that the originals mostly prospered and bred to start new generations.

To make up the 90-minute format required for the stand-up film lectures I produced a three-part program that I named The Call Of the Running Tide. Part 1 was on the first women’s team to go into saturation in an underwater habitat. The exercise was called Tektit II. Dr. Sylvia Earl was the leader. Part 2 focused on the first deep divers for black coral in the Hawaiian Islands. Part 3 was about the life and times of a New England harbor seal, Andre. When I was shooting 3000 Years Under the Sea I wanted some background shots of the Bay of Salamis where, in 480 BC, the Greek navy annihilated the superior fleet of the Persian king, Xerxes. I was guided by a young naval officer who assured me he knew a fine spot at the top of a long, high hill that overlooked the bay. We climbed for what seemed hours in the unrelenting Aegean sun, lugging tripod, camera case and other paraphernalia. Reaching the top we discovered no view at all. Higher hills lay between us and the historic bay. I ended up shooting one of those wonderful illustrations in National Geographic magazine. It showed Xerxes, himself, seated on a golden throne at the top of the right hill, watching his go down the tubes.

Blue Water, White Death was a stunning film for many reasons. How did you get involved initially?»I knew Peter Gimbel. We were friends. He visited with us in Maine during the summer of 1964. There, in the evenings by the fire in the living room we planned the outline for the production of Blue Water, White Death. It was originally planned that I would co-produce the film with Peter. However, Peter had the connections with CBS for the sponsorship and the money and time to start the physical preparations for the production. I was still on the lecture circuit and soon after (1965-’66) took my family away for the year in French Polynesia. That left Peter with the entire load. When I returned I demoted myself to Associate Producer and Underwater Cameraman. On Peter’s shoulders fell the full burden of forming the team, designing the special cages and camera systems. He threw himself into the project with total dedication and personal enthusiasm. It was Peter’s show. His energy and enterprise made it happen.

Swimming with The Biggest and The Best!

Swimming with The Biggest and The Best!

How was the rest of the team selected?»The rest of the team was composed in part of personal friends and professionals like Ron and Val Taylor, Jim Lipscomb for topside camera and Stuart Cody for electronics and equipment maintenance. Peter signed them on by their reputations. What were they like to work with on such an extended project?»The project took almost a full year in the field and another year for preparation. The group was remarkably compatible. Of course there were some dust ups. The most benign family could hardly avoid times of lost patience and personal differences living on a small ship for weeks and months on end. I think we came off very well. Peter led by example. He was fearless at times. Most often prudent. Every member had at least some sense of humor and that is a great leavening force. differences living on a small ship for weeks and months on end. I think we came off very well. Peter led by example. He was fearless at times. Most often prudent. Every member had at least some sense of humor and that is a great leavening force.

Why did Gimbel choose to locate in South Africa instead of looking for the Great White shark in Australia as the Taylors suggested?»I do not recall why Peter did his major reconnaissance to South Africa instead of South Australia, a known haunt for the Great White and an area of White shark encounters, pioneered by the Taylors. In South Africa he was advised by the Union Whaling Co. that their whalers encountered legions of Great White sharks that fed on the whale carcasses before they could retrieve them. The Union Whaling Co. was shore-based in Durban. They could provide a retired whale hunting ship, the Terrier Eight, to join their fleet, provide a base for our team, and cooperate with us to the fullest. That looked good to Peter. One misunderstanding proved critical and only evident when we were on location there. The sharks guaranteed by the whaling company were Oceanic Whitetips, not Great Whites. As it turned out the experiences we had with the Oceanic Whitetips (Charcrinus longimanous) were the most dramatic and certainly the most harrowing in our months of diving.

Valerie Taylor’s diary shares some frustration at the film process and at Gimbel. What was your perspective as the oldest member of the principal crew and a producer?»Gimbel was strong-willed, so is Valerie. I remember incidents that occasioned strong differences and tempers on edge. I would rather not reflect on them or review them. In my many years of experience and among those I most value, being a part of that splendid adventure is at the top. I would not have missed a day of it. I prefer to remember it that way and, indeed, I do.

You and Gimbel actually gave up your salaries at one point to get the company to complete the film. How did that come about and did the final result make it up to you both?»There was a clause in our contract with Cinema Center films that as, in fact, quite standard for productions. It specified – as I generally recall – that if a certain amount of the production was not completed in a time proscribed by the contract, further budget money would be withheld. Peter and I agreed to forfeit our salaries until the film was completed as a show of faith. That placated the backers. We were ultimately recompensed.

No diver had ever left the safety of a cage with large numbers of sharks back then. You guys swam out into hundreds of feeding sharks. Who made that call and why?»

Our first day on location with the sharks next to a sperm whale carcass was spent inside the two cages. Peter and Valerie shared one cage. Ron and I were in the other. It was evident that shooting from the cages was cumbersome, the action much circumscribed. On the second day Peter exited his cage without any forewarning that he was going to do that. I thought it was dangerous for him to be so exposed in the open with a large number of the big Oceanic sharks cruising about. I exited my cage, thinking to cover him. I was, in fact, scared to death. Peter admitted later that he was, too. But it was the right thing to do.

While the movie earned lavish critical praise, it has largely been unavailable since the early 1970s for the next generation of divers to view. What happened to the rights and how can someone see it today?»Blue Water, White Death vanished from view and never was marketed as a video cassette. The reason: Cinema Center Films, the producer, sold their entire library to Paramount Studios. That library included a John Wayne feature, another with Dustin Hoffman, and several others that were recycled in video sales. Paramount put our feature in storage where it still remains. Efforts to buy the TV rights have come to nothing. Paramount is uninterested. It’s been over 35 years since it was first released. Has any diving film ever equaled its breakthrough sequences since in your opinion?»Hans Hass and Cousteau produced theater-released features that certainly had the impact of Blue Water, White Death on the public. That I know of there have been no feature productions the equal of it since for theater presentation. There have been a number of fine documentary series produced for television. The latest, The Blue Planet, is more than a match for anything we did.Howard and Michele Hall’s marine animal series, Secrets of the Ocean Realm, is without peer.

What would you have done to make it better today?»The action and the range of the story make it unique both then and now. Cameras and optics have advanced, of course, and there are exciting marine life subjects that have emerged since our time. Had we known about the Great White shark scene in South Africa off Cape Town we would certainly have included that. But we were breaking ground, bringing that magnificent, supreme predator to the public eye for the first time. That perspective would be hard to beat today. Incidentally, we were on the island of Grand Comoro off the east coast of Africa in 1969 when we heard that the U.S. had put a man on the moon. That certainly beat any scenario we could come up with.

Breath taking Photography

Moving to another subject, I noticed that you supplied many of the photos for the book about the orphaned harbor seal, Andre. How did you come to meet Harry Goodrich and Andre?»Harry Goodrich lived in Rockport, Maine. I lived diagonally eastward across Penobscot Bay. I had a fast boat. With easy weather I could make it to Rockport in a little over an hour. Harry and I were among the very few who had Aqua-Lungs in Maine. I can’t recall how we met. I am sure I sought Harry out. We became good friends, dove together, and had family visits. Harry’s wife, Thalis, made pies that caused strong men to sob aloud. I would shamelessly telephone that I was going to run over by boat and thought I would be there in time for lunch. I was with Harry when he caught Andre, in a long-handled crab net by the ledges off Rockport. Andre was raised with the family, actually had his pad on the kitchen floor during the winter months while he was still a pup. The whole scene was so compellingly charming that I shot a segment of one of my magazine format lecture films about Andre and the Goodrich family. Andre not only made Harry famous but also provided him with satisfying, compelling purpose and self-esteem that his profession as a tree surgeon could not provide. With Andre, Harry achieved celebrity status. Hollywood some years later made a film about the Andre story and shot it on the West Coast with a sea lion. Andre was, of course, an honest New England harbor seal. I never saw the movie but I know that the publicity afforded great pleasure to the Goodrich family.

When Hollywood took on the daunting project of making Peter Benchley’s The Deep into a movie, how did you get involved?»Peter and I became good friends when he moved to Princeton after the publishing of Jaws. Our houses were within a few blocks of each other and we had many adventures working together for ABC, The American Sportsman show. So it was natural that Peter would introduce me to Peter Guber, the producer of The Deep and urge I be contracted to do the underwater camera work. I was accepted and brought Al Giddings in with me and he accepted on the condition that we equally share the credits. You and Al Giddings were designated as co-underwater directors. Did that work?»Al was an old friend with whom I had stayed many times in Berkeley when I was lecturing in the San Franciscoarea. I knew his capabilities. He was far better qualified for bringing together a support team and preparing the cameras, lights and diving equipment than I was. He took charge of the logistical preparation for the shoot, designing the housings for the 35mm cameras as well as the lights. Al, with enterprise, initiative, creative energy and a capacity for taking charge way beyond my range, did – indeed – take over. Chuck Nicklin and I in effect became second cameramen. Of course, I was personally injured and humiliated (laughing). At the same time there is no question that the better man for the job seized the reins. My input hardly justifiedsharing the same credits with Al.

Peter Yates, the movie’s director, had made such action films as Bullitt with Steve McQueen that became the standard for action films and car chases. How did a non-diver get on with you two when he couldn’t actually direct or even see the film’s most exciting sequences as they occurred underwater?»Peter Yates was an excellent director. And became a good friend. He quickly learned to dive and very soon into the production was personally present on the underwater sets. He was hard-wired for communication to the surface with his directions relayed to us through a transponder. Thus he extended his direction into the underwater second unit. Only when we went to Australia and on to the Coral Sea to shoot the shark sequence with doubles were we on our own. Al, of course, took over direction.

Jackie Bissett and some of the other actors were not divers before filming began. How did you get around that obstacle?»

Lou Gosset was an experienced diver and had a fine time diving with a

Robert Shaw was a notorious character that never hid his love for whiskey, on and off the set. What was it like to work with him?»Robert Shaw came to the production with the largest celebrity status. No one begrudged his special housing. That comes with stardom. He was certainly an alcoholic and we were aware of delays in the shooting because of that. We only encountered his temper once. He had his own trailer on the set and used it during the day. My son Gordy, was an underwater grip, making more money on the Hollywood budget than he had ever dreamed of. At the same time he was reluctant to use the very liberal room and board per diem that enabled most of us to stay at the South Hampton Princess Hotel. So he eyeballed Robert Shaw’s empty trailer, discovered he had access to it after dark and so nested down there. I had no idea he was doing that or later how long he gotten away with it. One morning he overslept and was discovered by the great man. Shaw would have the cheeky grip fired from the production. Cooler heads prevailed. A bit of nepotism also helped.

Bermuda Set

How did you like filming on the 1867 wreck of the Rhone in the British Virgin Islands?»I knew the Rhone well, having dived and filmed there previously. Parts of it were wonderfully photogenic and readily accessible. All other divers and commercial dive operations were restricted from diving on the Rhone while we were working there. Since our production there lasted over three weeks you may imagine the local divers would have liked to nuke us all. Dealing with currents and varying visibility conditions must have been a challenge?»The Rhone is so popular as a dive sight that it is hard-worn today, not just by the legions of divers but by storms as well. When we were on it we generally had excellent visibility and calm seas. The forward part of the wreck which provided our interior takes was deeper than we might have wished, requiring long decompression times that found us hanging off after dark. All the close action interior takes were, of course, done in the underwater set at Bermuda.

Did you find the underwater set built in Bermuda to be as easy to work as it looked?»The underwater set in Bermuda provided the only physical structure in which we could light, prepare and shoot the complicated scenes. Toward the finish of the shooting, which lasted almost a month, the plastic composition used to seal the walls of the million-gallon tank that had been created started to disintegrate. The marine life that had been introduced as props began to die. The water become so toxic, despite renewal from the sea, that we all developed ear infections. Our second unit part of the production was a “wrap” just in time before the set totally deteriorated.

“There is a tide in the affairs of men that taken at the flood leads on to fortune. Omitted, all the journeys of their lives are bound I shallows and in miseries. You must take the current when it serves or lose the venture”. (Hamlet)

Howard Hall credits you with getting him started in professional underwater filming. Who mentored and influenced you?»I was certainly influenced by Hans Hass and Jacques Cousteau. I picked up Hass’s book, Diving To Adventure, right after I mustered out of the Navy in 1946 and was much fired by it. That was the opening shot. But it was Cousteau’s Red Sea article in National Geographic that was the catalyst for me to try the sea and diving as a vocation. I was a farmer in Maine at the time. The year was 1953. I was bored with farming and still too young to spend the long winters making birdhouses in my workshop. That article started me thinking about taking a chance, making a move. Shakespeare had something to do with it too. In Hamlet he wrote, “There is a tide in the affairs of men that taken at the flood leads on to fortune. Omitted, all the journeys of their lives are bound I shallows and in miseries. You must take the current when it serves or lose the venture”. So I re-mortgaged, shot my wad on building a boat that I designed for diving and set up in the Bahamas. The Bahamas years (from 1954 to ’59) hardly broke even. But they were the foundation for a vocation that I have never regretted.

Do you dive with nitrox or rebreathers now?» All the dive boats I work with now have nitrox. I subscribe to it entirely and only return to air if I want to go deeper for some reason. The reasons seldom appear. I use the standard Dräger rebreather only occasionally. I am certified for it and will use it when I return to Cocos Island. I should use it more, especially since animal behavior is my major focus. I probably will in the future. When you started the Nikonos had never been released. And underwater motion picture

You are still actively diving and sharing the experience with fellow divers by leading custom tours. Where are your favorite dive locations and what are your favorite liveaboards?»My favorite dive areas are New Guinea, Malaysia, Indonesia and Fiji. I also return almost every year to Palau and love diving there. Those areas have yielded the most exciting macro encounters, and macro is my favorite subject these days. The Lembeh Strait at the northeast end of Sulawesi in Indonesia and the Kungkungan Bay Resort that serves it is the most exciting dive location I have encountered. I will decline rating liveaboard dive boats with which I work. They are all excellent with fine crews. The locations vary in their appeal to me but I am pleased with all the boats I work with.

You’ll be 84 years old in early 2007. Any plans to slow down or take up golf?»I will give up diving when I no longer enjoy it. It will almost surely be when I am no longer physically able to dive comfortably and safely. Leni Riefenstahl, the “super woman” survivor of the Third Reich was diving at the age of 91. If I start main-lining Geritol I may make it. When the oldest living human with a certified birth certificate died in France at the age of 124 the press had interviewed her the previous year. When asked what she had to say about her future, she said, “Not much!” If a shark eats me on my next round I will be sorry to pack it up but grateful for what the sea has given me during a long, productive and satisfying career. Tennyson wrote of Ulysses, “How dull it is to pause, to rust unburnished, not to shine in use as though to breathe were life.”

FOR ANYONE LUCKY ENOUGH TO CATCH ONE of Stan Waterman’s personal appearances, you undoubtedly came away with a lasting impression of his wonderful speaking presence and gift for oration. I remember my own feelings after seeing him for the first time some thirty-five years ago: it was like listening to Lincoln or Churchill… but with a better vocabulary. And Stan talked about diving, my passion, in a way that no one else could.

Stan, of course, is the U.S.’s first pioneer of diving. Someone once suggested that he was the “Jacques Cousteau of American diving” and was promptly corrected by an observer to note that “Cousteau was actually more like the Stan Waterman of France.” It’s a fair statement. Over the years, Stan has been a prolifie filmmaker winning multiple Emmys and gaining his first international fame in the iconic 1971 release of Blue Water, White Death. Collaborating with Peter Gimbel, he co-produced, filmed and starred in this groundbreaking documentary about their quest to find and film the Great White shark in its natural element. Five years later he joined Al Giddings as co-director of underwater photography on the Hollywood blockbuster hit The Deep. In 1994 the Discovery Channel honored him with a feature two-hour special aptly named The Man Who Loves Sharks. The September 12, 2005 issue of Sports Illustrated has a profile of Stan remembering his first appearance in the magazine on its cover in January 1958. It’s hard to find a serious diver who has not been touched in some way by this gentle and eloquent man’s creative works But Stan is truly in his element when you discover him through his writings. That’s not hard to believe when you consider that he actually studied under Robert Frost at Dartmouth. Throughout his lengthy career, he has carefully chronicled his underwater rites of passage in a widely published series of articles, features, anecdotal musings, and interviews. Now for the first time, a nearly complete body of that work is available in one book spanning his earliest youth to the present. For years, Stan’s friends have urged him to release just such a collection and I’m glad to note that he finally capitulated. New World Publications, the brainchild of Ned DeLoach and Paul Humann, made their reputation with the superb series of marine life and coral identification books. Sea Salt is their first offering in this genre.

Opening with forewords by Peter Benchley and Howard Hall, the reader is treated to a series of chapters in the book’s first half that unveil Waterman’s earliest development as his interest in diving and the sea awakens. The second half of the book contains the essay series originally begu with Ocean Realm magazine in the 1980s and that I continued with Fathoms. I consider myself something of a Waterman aficionado and still was surprised to discover original works contained here that I had missed over the years. At 288 pages with 72 photos, the hardback tome has a rich treasure of adventure, opinions, shared observations on interesting friends and companions, the thrills of behind the scenes happenings on film and dive projects, as well as soul-baring reflections on his family and the strains that he sometimes brought them due his globetrotting zeal in pursuit of his diving muse. References are often made to the skill of master photographers who “paint with light.” Waterman goes far beyond that. He paints a richly diverse canvass of life experiences with only words. One of the most poignant memories he shares describes an outing off Corsica in 1950 when the motivation for many early underwater explorers was to hunt fish:

“I entered the Mediterranean with mask, fins, snorkel and Arbalete speargun, my first dive on the old world side of the Atlantic. The recollection is so clear that it might have been yesterday. I was immediately surrounded by a great school of silver jacks. They flashed in the sun as they turned in unison, circling around me. They were friendly, curious, beautiful ambassadors of the Mediterranean world. And how did I greet them? I fired into the middle of the school, wounding one and frightening away the entire lot. And such was my fear of sharks and the unknown in the deep blue water beyond my reach that I nervously swam for the jetty and scrambled out of the water, happy to have escaped alive from this daring adventure. There was no shame in having violated that peaceful world into which I had intruded. I was rather proud of myself for having at least winged a fish. Yet the memory of that violent, thoughtless act still evokes an unpleasant sense of shame today.” Sea Salt is a magnificent volume. It will excite, sadden, thrill and mesmerize the reader with tales of a singular life by an extraordinary man who has emerged as diving’s most articulate and sensitive spokesperson.

Family and a Career

Family and a Career

Swimming with The Biggest and The Best!

Swimming with The Biggest and The Best!