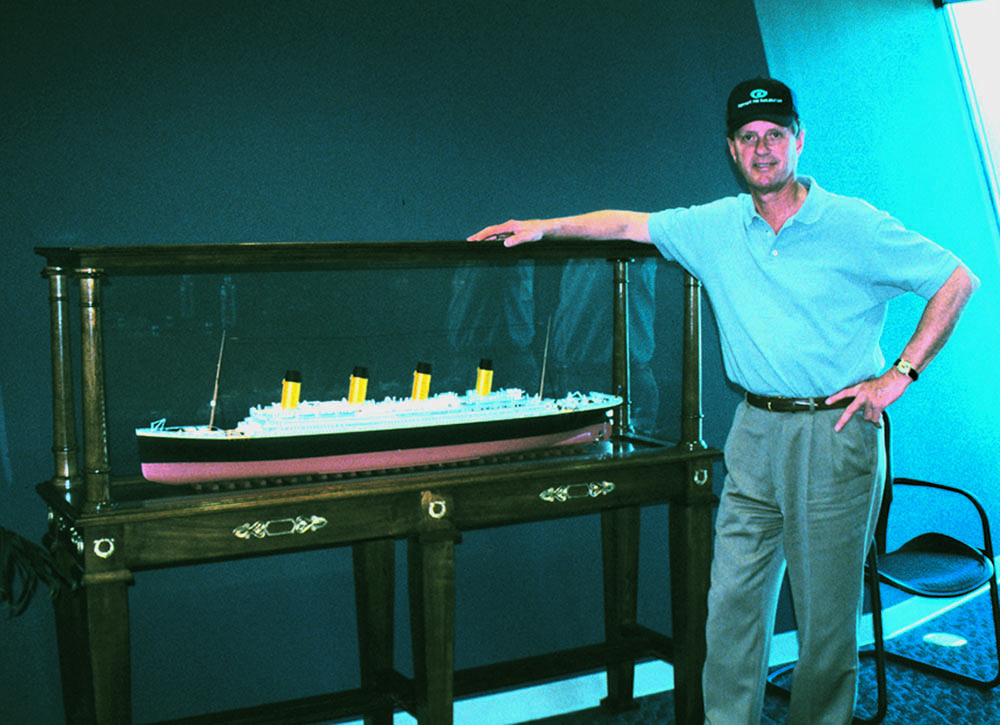

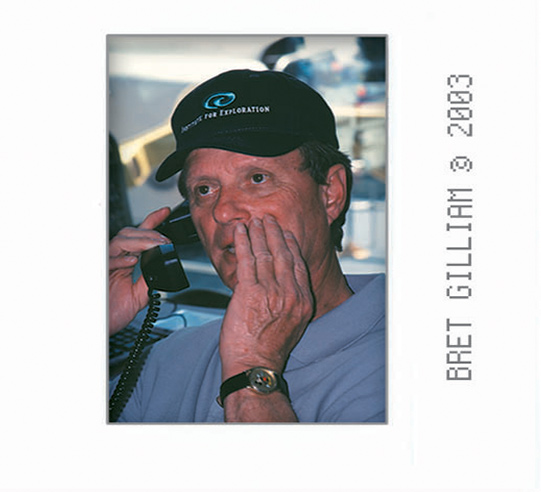

Ballard’s offices are located at the Institute For Exploration (IFE) at the Mystic Aquarium in Mystic, Connecticut. As summer crowds of eager visitors thronged through the turnstiles of the IFE exhibits at the rate of nearly a 1,000 an hour, I navigated my way past a full-sized replica of a support ship with a full-scale submersible on its aft deck “floating” in its own massive water basin. I then rendezvoused with an eager staff member who shuttled me into a private elevator and up to Ballard’s inner sanctum. Catching up with Dr. Bob Ballard, probably the world’s apex ocean explorer, is roughly akin to attempting to lasso a tornado. The man moves at the manic pace of a Jack Russell terrier that had way too many cups of coffee. It’s not hard to see how he maintains an athletic frame well into late middle age. Since both of us were on a tight schedule that day (he was off for a horseback riding vacation in Jackson Hole, Wyoming and I had to depart for Cocos Island to ride sharks), I outlined what I needed for some photo opportunities before settling down for the interview Q&A. Before the last words were out of my mouth, Ballard was off with the urgent stride of an Omaha insurance salesman late for his first lap dance at a Las Vegas convention.

I streamed behind in the turbulence of his wake as we set up shots in his office, by the submersible exhibits, at a control console for some of his many remote video streams from cameras in the wild, and on a sprinting slalom course through the fascinating museum of oceanography he has put together. In less than 20 minutes, I’d seen the entire Institute For Exploration, burned four rolls of film, met about a dozen staff and assistants, climbed over the exhibits including re-created models of Titanic’s radio room, PT-109’s bridge, and probably lost five pounds through perspiration alone. We ended up in Ballard’s spacious office suite dominated on one wall by a 30-ft. long map of the world and an opposite wall of glass overlooking the outside exhibits. As he sat at his desk politely answering my questions and reflecting on his unique career, a large plasma TV screen streamed a live video from a rocky kelp bed off California where two kayakers were ogling a sea lion colony. Aside from being a fascinating intellect, Ballard is perhaps the premier “gadget guy” I’ve ever met. He views advances in imaging technology as the ultimate tools for exploration. He’s also a font of insightful quotes that help the layperson find some perspective between hype and science. “Exploration is a discipline,” explains Ballard. “Look at Charles Darwin, Christopher Columbus, and one of my heroes, Capt. James Cook. They were sent forth as disciplined observers. Adventure is bungee jumping off a bridge; exploring is mapping the canyon under the water of that bridge.” This perspective dovetails nicely with the IFE’s mission statement: “To inspire people everywhere to care about and protect our ocean by exploring and sharing their biological, ecological, and cultural treasures.” Ballard’s just the guy to make all that happen. He has a Ph.D. in marine geology and geophysics from the University of Rhode Island. He spent three decades at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute where he helped refine and develop the use of manned submersibles and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) for marine exploration. With 13 honorary degrees, the rank of commander in the Naval Reserves, and a litany of cutting edge research expeditions that have rightly established him as “da man” in the niche of modern ocean exploration, Ballard had already made a career’s worth of marks when he made himself a household name with the discovery of Titanic’s wreck over two miles deep in 1985.

He notes ruefully, “After I found the ship, I got some 16,000 letters from children.” This may have been the richest treasure he has discovered: the imagination of a whole new generation of potential scientists, explorers, ecologists, etc. that is growing up in a new age of information and access. Ballard has been involved in over 110 expeditions that included break-through research in proving the theory of plate tectonics, the discovery of hydrothermal hot water vents, the pioneering use of submersibles and ROVs as scientific tools, and a host of other pure science accomplishments that should have left a footprint in the public’s consciousness along the way.

“No child had ever said to me, ‘that’s cool!’ about my work,” he reflects. “But as soon as I find an old rusty ship, I’m inundated.” Go figure. Ballard’s Jason project now allows nearly two million students and 33,000 teachers to join him in his work through the modern miracle of telepresence… each year! His new facility in Mystic carries that educational mission a notch farther and his imagination continues to grow.

“When I first arrived in 1967, the best way of getting to work was submarines. So I was a pioneer in using submarines to explore the deep sea. During the course of that work, it became glaringly obvious that physically going to the ocean floor was not going to work. With the average depth of the ocean at 12,000 feet, it used to take me two and a half hours just to do the descents. That’s a five hour commute round trip! My average bottom time was three and half hours and I could only explore about a mile. It was ludicrous. “Since 71 percent of the planet is under water, and there are only five submarines in the world that can go to that depth, and each of them can only carry three people… this means that on a really good day, you might have 15 people exploring.

“Argo-Jason was named in honor of Jason and the Argonauts, the first explorers of western civilization. This allowed us to put robots under the ocean and leave them there, around the clock. Instead of three hours, we now had 24 hours, and could do 10 times the work. Instead of three people crammed into this little metal ball, freezing to death with the angst of ‘we could all die down here,’ the idea was to build a control center and do it all by telepresence. Now I can turn on a

From Geologist to Discoverer

You began as a geologist in physical sciences then went on a career path to becoming a classic scientist. Did you perceive a change to oceanography when you did graduate work at the University of Hawaii?»The change came much later when I was asked by the Navy to survey the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Thresher and Scorpion, followed then by my search for and investigation of the RMS Titanic. That changed my career direction from geological oceanography to archaeological and historical oceanography. When and where did you learn to scuba dive?»I learned to scuba dive in Southern California in 1958-59. I was certified by the L.A. County Fire Department, if I recall correctly, since back then that was the only organization that could certify divers.

You spent time in Hawaii as a dolphin trainer and later commented that you felt the dolphins were training you.»It was interesting working with an intelligent animal. I discovered that kindness and affection was as powerful a motivator as food. You earned an ROTC commission as an Army officer but ended up being transferred to the Navy. How did that come about?»I was a graduate student pursuing a Ph.D. in Oceanography at the University of Hawaii and went down to the Navy Recruiting Office at Pearl Harbor to inquire about transferring. The Navy needed oceanographers so they took me.

Tell us about your first experience with deep submersibles at the Ocean Systems Group in 1966.»I was working for Dr. Andy Rechnitzer and Dr. Richard Terry. They were designing and building the Beaver Mark IV lock-in, lock-out submersible for Mobile Oil and wanted to use it for scientific as well as commercial purposes. My job was to dream up operational requirements for geological exploration and observe how that translated into the design. What was it like to work with Dr. Rechnitzer?» Great. He and Dr. Terry were both dreamers.

Alvin Group

The Navy threw a wrench in your academic path when they suddenly called you up for duty. What was that like being uprooted from sunny California and landing in the snowy northeast?»I loathed it at first, it was quite a culture shock but it proved to be a critical turning point in my career. The Navy assignment was your first introduction to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). How did you fit in?»I had helped in the original design of Alvin while working for Rechnitzer and Terry, therefore knew a lot about similar submersibles. I was also going to graduate school at USC and working for the Oceans Systems Group. The head of the Geology Group at Woods Hole was Dr. K.O. Emery who founded the Graduate School of Marine Geology at USC, so both groups accepted me and I was quickly put to work. Later it was Dr. Emery and Bill Rainnie who made it possible for me to return to graduate school at Rhode Island to receive my Ph.D. while making a living with the Alvin Group.

Was this your first experience with intense competition between various academics for funding?»That came later. At first I worked for the Alvin Group with the Office of Naval Research (ONR) funding. Originally it was the WHOI that brought you and the Alvin deep submersible together. What was Alvin’s history and mission at that time?»There was quite the buzz when I arrived at WHOI in March of 1967. Alvin had just found the H-bomb off Spain. As submersibles were still considered scientifically 1. Full-scale model at the Mystic Aquarium in Connecticut. 2. Artist’s rendering of Alvin 3. ROV Jason Jr. peering into one of Titanc’s starboard side cabins untested, the science community did not take them seriously. Alvin was also unable to dive deeper than 6,000 feet; therefore it was confined to dives on the continental margin while many other findings were happening in the deeper mid-ocean ridge.

What projects had Alvin participated in?»Besides the bomb search, Alvin was doing dives for geologists and biologists but nothing earth shaking. Can you share with us some of the first research projects you were involved in at WHOI?»At first, I went to sea with K.O. Emery and one of his previous graduate students from USC, Dr. Al Uchupi. They taught me a great deal about continental margin geology, submarine canyons, and the complex geology of the Gulf of Maine and its relationship to the newly emerging science of plate tectonics.

You had to deal with some raging egos that infiltrated some of your cruises and affected morale. What did you learn from those Ph.D. types that seemed to lack leadership?»Intelligence is not a substitute for leadership. In fact, the scientific community tends to produce poor leaders. Alvin and the NR-1 represented different approaches to submersible design, compared to older craft like Trieste.

Did you see the exploration potential right away?»Not so much an exploration potential in the case of Alvin as it can only cover a limited amount of terrain, but what made it unique was its ability to go to complex geologic settings and figure out the science associated with it. The NR-1 had exploration potential but it was highly classified, very expensive, and very uncomfortable to use.

Alvin and the NR-1 represented different approaches to submersible design, compared to older craft like Trieste. Did you see the exploration potential right away?»Not so much an exploration potential in the case of Alvin as it can only cover a limited amount of terrain, but what made it unique was its ability to go to complex geologic settings and figure out the science associated with it. The NR-1 had exploration potential but it was highly classified, very expensive, and very uncomfortable to use.

Alvin sank in 1968. What happened?»They were lowering the sub in its cradle with the hatch open when the forward cables snapped, throwing the sub into the water with enough force to send it underwater and flood the pressure sphere. They were lucky to get out alive before she sank.

What was your first dive in Alvin like?»I had dove in Ben Franklin the previous year. The Franklin was very comfortable and could stay down for three-to-five days. My first dive in Alvin was in the Gulf of Maine and it was very frustrating because visibility was so poor.

While you were in New England you hooked up with the Boston Sea Rovers.»I was a young Ensign in the Navy when I went to my first Sea Rovers Clinic. Cousteau, Waterman, Giddings, and many others were there. It was the greatest collection of diving egos you could ever hope to meet. The annual gathering was full of energy and excitement, but as I would later learn, the focus of these clinics was not necessarily about the science of the sea, but rather the art of diving.

I understand that one of your first discussions about Titanic originated at a lobster bake with the Sea Rovers. Did you envision then that such a dive in a submersible was possible?»Yes. The project was named Titanius, not far off from Titanic. Alvin’s steel hull was about to be replaced with one made of titanium. The new hull would allow for an increase in diving depth. This meant Alvin could now reach the Titanic for the first time. Eventually you were forced to make a decision between a Navy career and pursuing your Ph.D. as a scientist. Was that a difficult choice for you?»No, I knew I had to pursue a Ph.D. Without one you can’t lead. You have to work under someone else and always play second fiddle. How did you become the designated fundraiser for the Alvin projects?»In 1970, ONR told Bill Rainnie he had three years to replace ONR’s funding with new, non-military funding sources. I was convinced it could be done so Bill hired me to do it and I did. Describe your feelings upon first viewing the deep water Jonah crabs from a submersible.»It was on my first Ben Franklin dive. We had dropped a bait can to attract life and when I saw the 55-gallon drum completely covered by hundreds if not thousands of feeding crabs… I decided never to be buried at sea.

Continental Drift

Later you became embroiled in the debate among scientists over the theory of “continental drift.” These differing opinions sparked heated and sometimes rancorous discussion, didn’t they?»That was a very exciting and heady time which truly demonstrated how exciting science really is and that diving should be more than just a great story at a Sea Rover clinic. Didn’t Alvin help to confirm your theory about continental drift?»Yes, but only in a supporting role to a lot of other tools. You changed the way Alvin and other submersibles were utilized by trying to pinpoint their focus on specific marine areas.»During Project Famous, Alvin demonstrated that having human eyes and hands on the bottom of the ocean was the ultimate final step in underwater science.

On one of your earlier Alvin dives you were nearly crushed by a huge boulder? How deep were you and how did that happen?»It was 1976 and we were diving in the Cayman Trough. We were working at the base of a giant cliff pulling rocks out of the rock face. As we moved up the face, we realized that the rocks we were trying to pry loose were holding up a massive boulder just above us. That was a scary moment. Thank God we were unsuccessful in prying them loose! Alvin was originally only designed to go to 6,000 feet. You pushed for the submersible to be certified to twice that depth. How did you accomplish that?»The Navy wanted to build and test a new titanium sphere so we convinced them to use Alvin as a test bed for that program. Tell us about the pioneering work you did on Famous?»Famous was the turning point in deep submergence science. We were under scrutiny by the entire oceanographic community and they were convinced it would fail. Fortunately, the critical science could be done over a very small area, ideally suited for Alvin. The rift valley of the mid-ocean ridge along the plate boundary was rugged and complex, yet less than one mile across.

You also had a narrow escape when a fire started on a deep dive. What caused that and how did you deal with it?»I was diving in the French bathyscaph Archimede in 1973, a year before we used Alvin, on a series of preliminary dives in the Famous area. We were on the bottom at 9,000 feet when an electrical fire broke out inside the pressure sphere. The sphere quickly filled with toxic black insulation smoke. Our eyes and lungs were burning as we dropped out weights and headed up. It took one and a half hours to surface. I was sick with strep throat, which only compounded my misery, but it was a historic dive.

Did you feel vindicated when finally earning your Ph.D. after all the challenges to your work?»Getting my Ph.D. was the end of one phase in my life and beginning of a new one. Without it, too many doors were locked. How did Angus come about?»Angus was developed by Dr. Bill Bryan and Dr. Joe Phillips at WHOI for Famous to conduct a series of film runs across the rift valley floor. I went on to perfect it as a search tool for Alvin. We used it in 1977 to find the first active hydrothermal vents and in 1979 to find the first “Black Smokers.”

You discovered publicity aided funding for your exploration projects. But this also brought criticism from the old school academics. How did you deal with that element?»Working for National Geographic was a blessing and a curse. Every Sea Rover loved National Geographic while most oceanographers thought doing anything with them was a waste of time. I later discovered it was much more complex than that. The fact was most oceanographers were doing things that the public and National Geographic had no interest in. To make matters more difficult, the press, National Geographic included, portrayed science as an “I” profession when in reality, it’s an “us” (it’s a collective scientific effort). The press would single out an individual and make them a hero. This made some rightfully angry and others wrongly jealous. The discovery of the hydrothermal vents off the Galapagos was another landmark.»It was a great expedition and it was clearly the result of much hard work by many great scientists.

The Underwater Threat

Didn’t you also nearly have an accident by approaching a hot water chimney vent?»We didn’t realize at the time how hot the vent water was until Alvin returned to the surface and we saw the heat damage. It had melted down to the foam, close to the viewport on the port side of the sub. We then became very careful when working around black smokers on future dives. It could have been a disaster had we let the hot fluid hit our view ports inches away.

Although you were a huge advocate of deep submersibles, you eventually favored a different means of observation in deep ocean zones by utilizing unmanned vehicles. Did this cause a rift between your ideas and the manned submersible factions?»My conversion to remotely operated vehicles made me a traitor in the eyes of the deep submergence community. It was a fraternity that felt I had deserted them. The physical act of diving was such a part of deep submergence that not doing it, or worse yet, replacing it with robots threatened to emasculate those who utilized remotely operated submersibles. I was more interested in why I was diving as opposed to the pure act of diving. Diving was becoming “old hat” for me and I saw so many people continuing to “pound their chests” about the dangers of diving when in reality air travel took more lives. People would return from a dive then talk about it but never tell me anything interesting about what they saw. It was too macho a world for me to live up to the rest of my life – a Sea Rovers Clinic gone to the extreme.

Different Methods Used and Created

You were left to conceive, design and build the Argo-Jason system.»In 1979, we returned from the Galapagos Rift with the first biologists to see the exotic marine life living around the vents. We mounted a new digital color camera on Alvin’s arm to test. I had my back turned to the view ports and was looking at a TV monitor when I noticed the biologist was doing the same. A light went off in my mind. Why were we down here if the biologist thought the view on the screen was better than looking out of the sub’s viewport?

In searching for the wreck of the submarine Thresher you had an epiphany about the trajectory and trace debris left on the bottom that changed your methodology for looking for wrecks. Can you explain how you changed the accepted theories and why?»Prior to that experience, the standard way to look for something on the bottom was to use a side-scan sonar. But in complex bottom terrain with many targets, deep canyons and narrow ridges, a side-scan sonar can quickly become difficult to use. In such terrain, only the largest of targets can

The Discovery of The Titanic

Although many artifacts of the Titanic are nearly perfectly preserved, there are no traces of human remains. Why?»Remember the Jonah crabs? People are eaten and their bones are exposed. The deep sea is undersaturated in calcium carbonates that make up bones. As a result, bones dissolve quickly leaving only the inedible shoes behind. Inside wrecks you’ll find bodies and skeletons, but not outside unless you are in the Black Sea, which has no oxygen. What are your thoughts on the practice of taking laypersons on submersible dives to the Titanic if they ante up the fee?»I think visiting the Titanic by lay people is wonderful. It’s no different from going to see the Arizona in Pearl Harbor. My concern is for the damage to her decks that will result from the subs that land there and leave things behind. I’ll give you an update next summer when I go back for the first time since finding her. Did you like Jim Cameron’s movie Titanic?»Yes. Great movie! You and I are both members of the prestigious Explorers Club. Cameron was just inducted and given a special award, how does this sit with you?»I think Jim is a great moviemaker and an innovator of filming technology. I wish I had his cameras, lights and his budgets.

You’ve had a long relationship with the National Geographic Society and produced some great articles and films for them. You’ve had your differences along the way including a ruckus over the first press conferences following Titanic’s discovery in 1985. How do you balance the relationship with sponsors?»I have a wonderful relationship with the National Geographic Society. I am one of their Explorers-in-Residence and receive more support from them now than I have ever received in the past. I hope it goes on forever. National Geographic management stood with me during the Titanic press flap with the French and our sub-sequent return to the Titanic the following year, others didn’t. Please enlighten us on the discovery of the Bismarck. Was it a similar project to Titanic?» Same visual-search strategy just a larger area and with another sunken ship close by that threw us off the first year, we recovered the second year and found her. Before one can explore a ship, one needs to find it, and that is the hard part. Exploring a wreck site is the reward one is given after the hunt ends. And finding the German battleship Bismarck was not easy. In fact, it was the most difficult hunt I have ever conducted, and that includes finding the RMS Titanic, the USS Yorktown, and PT-109.

What made the search for Bismarck difficult was the depth at which the ship lies–more than 14,500 feet of water–the uncertainty of its location, the terrain in which it had come to rest, and the avalanche it set off on impact with the seafloor. Unlike other seekers of shipwrecks, I adopted a hunt strategy for finding shipwrecks in the deep that involved constant visual contact with the bottom. My colleagues questioned this strategy, relying instead upon the age-old technique of using a side-scan sonar to search. Operating in total darkness, video cameras can only see a short distance, 30 meters at best, while 100 kHz side-scan sonars can reach out more than 400 meters to a side. Why would I want to search with a camera? Back in 1984, the U.S. Navy was thinking about disposing of the nuclear containment vessel that housed the reactors in retired nuclear submarines. We were concerned about the adverse affects the reactors might have on the deep benthic environment. For that reason, the Navy wanted to investigate the nuclear reactors of the USS Thresher and USS Scorpion that have been lost and still never found, in the 1960s. I was called in to see if I could find them using my new camera sled Argo.

A Fundamental Discovery

While mapping the wreck sites, I made a fundamental discovery. Shortly after sinking, both subs imploded catastrophically thousands of feet above the sea floor, creating a mass of debris of all weights and sizes. As this material sank, underwater currents carried the lighter debris more than one mile away from the heavier objects, creating a long trail of wreckage. More importantly, side-scan sonars were unable to detect these light objects while a camera could. Both Titanic and Bismarck released a tremendous quantity of debris into the water at their moment of sinking. Knowing the currents in the area, I could predict the direction in which the debris would have drifted and lay out search patterns that crossed the debris field at one-mile intervals. This made it possible to move through the area very quickly. For Titanic, this strategy worked fantastically. Once I located the debris field, I was able to follow it to the shipwreck. For Bismarck, however, the method proved more difficult. During the 1988 search, I picked up a debris trail that led to another ship, a larger wooden schooner that had sunk years before. The summer search window was lost. The following year, I picked up another debris field but it led to a large depression with nothing in it. Had Bismarck been buried by its own impact? No, Bismarck’s impact with the seafloor had set off a giant landslide, carrying the ship downslope, requiring more time to finally locate her. As I got close, I saw its skid marks on the bottom, surrounded by hundreds of German boots.

Except for a small portion of the stern, the ship was upright, intact and in an amazing state of preservation. The swastikas on her bow and stern decks were still there. We examined the mighty armor belt looking for signs of damage. We found none. As I wrote in my 1990 book, the Discovery of the Bismarck, “alongside the hull we could see evidence of hits from the British secondary guns. In some cases, the shells had splattered like bugs on a windshield, seeming to leave the armor intact.” But what struck us most as we returned to port was the absence of implosive damage to her hull like that on the stern of Titanic, the result of a ship sinking before being fully flooded. From the integrity of the wreck, it would seem that Bismarck sank well after her watertight compartments had been blown open to speed her final journey to the ocean floor. The first question I was asked by the British press was, “Did we sink her or was she scuttled?” To their horror, I answered, “I believe she was scuttled.” But only after further exploration would we know for sure. You’ve extensively explored the shipwrecks of the Solomon Islands’ Iron Bottom Sound. You later turned your attention to locating the wreckage of John Kennedy’s PT-109 off Gizo in the northern Solomons. How did that search differ from your hunt for other wrecks?»PT-109 was a true needle in a haystack. It wasn’t where everyone thought, so what’s new? And we didn’t have much time to find her. The bottom currents were very strong and she was mostly buried by drifting sand dunes.

The Kennedy Family

How did the Kennedy family feel about your expedition?»The Kennedy family was great and fun to work with, particularly Max Kennedy who went on the expedition with us. Our strongest support came from Senator Edward Kennedy and his great staff. You’ve also been conducting explorations in the Mediterranean for ancient shipwrecks.»After finding many contemporary shipwrecks like Titanic, Bismarck, PT-109, Yorktown, etc. I began to wonder about the fate of older and potentially more important ancient shipwrecks. This thought has now set me on a new path. I’m now convinced that the deep sea contains more ancient history than all of the museums in the world combined and I want to help unlock that underwater museum for the world to enjoy and learn from. Do you believe that, as a society, we are spending too much money on space exploration and not enough on marine and ocean exploration?»I think space exploration is something our nation should do including putting humans on Mars. I simply think we, as a society, should be spending a similar amount on ocean exploration.

What’s your opinion on the state of manned submersible and ROV units today and what would you like to see next?»The Ocean Science Board of the National Academy of Science has been asked by the National Science Foundation to deal with the furtherance of deep submergence technology. That study is underway and I’ve made a specific series of recommendations to the group but time (less than a few months) will tell. Their hearings are ongoing.

Graham Hawks’ Deep Flight submersible has gotten a lot of press. It exudes sizzle and sex appeal but do you feel it will it prove to be a useful tool for science?»I think it will provide people, particularly the lay public, with a wonderful opportunity to fly in the underwater world. I don’t think it will result in a great deal of compelling science, but that doesn’t mean Deep Flight submersibles shouldn’t be built with private money.

Bring us up to

Taking a Glimpse into the Past

Are wrecks graveyards to be left undisturbed or are they fair game for archaeological study?»It depends. There are wrecks… and there are wrecks. Some are important and many are not. I draw a line between a recent wreck and an ancient wreck. Recent wrecks have living survivors and living relatives of the dead. They need to be treated with respect for the

Should artifacts be studied and left underwater or brought up and preserved?»If there is something to be learned scientifically or archaeologically, then recovery is justified. Many of the ancient shipwrecks I found were commercial carriers with large quantities of the same object and in some cases, these objects are still preserved underwater. In such cases, only a few need to be recovered. The remainder is not going anywhere and is easy to locate should scientists need another sample. I think underwater museums should be created. It’s very expensive to conserve, guard and protect ancient artifacts forever. Forever is a long time! What about the ships themselves, such as the Civil War ironclad Monitor?»In some cases, bringing shipwrecks to the surface, particularly small ones, is the best way to preserve them for others to enjoy and that action is justifiable. But in the case of the Titanic, removing artifacts, particularly artifacts that can remain underwater for thousands of years (i.e. glass, ceramics, etc.) lessens the experience of others who follow. I think technology will soon make it possible to stop further degradation, in fact, even reverse it.

What’s this new project you’ve got going at the Mystic Aquarium?»It is the Institute For Exploration (IFE)/Mystic Aquarium and it has no endowment. Wish it did. Donations are accepted. IFE is dependent upon many sources including federal grants from the Office of Naval Research, NOAA, in particular, Office of Ocean Exploration, National Geographic Society, private donations, and 750,000 visitors that come to our exhibit center every year. For most of your career, you’ve had to chase funding from the Navy, National Geographic, National Science Foundation, etc. Will your new Institute make your exploration projects easier now?»The need to raise funds to chase your dreams will never go away. Columbus had to do it. Lewis and Clark had to do it. Peary had to do it and I, along with other explorers, am no exception. It’s a rite of passage.

What the Future Holds

You’ve recently embarked on a project for semisubmersible oceanic habitats. Do you see floating cities in our future? Is Waterworld just around the corner?»I don’t think a large number of people will live beneath the sea in ambient pressure habitats. That’s great for science and for industry but too expensive for the masses. I do believe that more people will move out onto the sea. They already are doing it on offshore platforms of the oil and gas industry. Tens of thousands of us do it each day. I foresee a time when families will begin to do it on vertical spar buoys like Scripps’ FLIP. It’s a matter of time and dropping costs. You’ve managed to carve out a fascinating career as an underwater equivalent of Indiana Jones. What advice might you give young people who’d like to pursue a similar path in ocean exploration?»I always tell young people to follow their dreams. Not their mother’s, father’s, or teacher’s dreams but their own. You need the passion of your dreams to get you back up on your feet when society knocks you down.

What are your new dreams?»I have always lived in two worlds. The world of deep submergence technology and the world of deep submergence science. It goes back to my upbringing by Andy Rechnitzer and Dick Terry and later by K.O. Emery and Bill Rainnie. In the world of deep submergence technology, I want to go to the next level in telepresence this summer when I begin the process of moving the diver to the beach so one can have infinite “bottom time.” Just think, if you come to Mystic in July and August, for 24 hours a day for 30 days you can be underwater in the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean diving on a series of ancient shipwrecks, working with those at sea as if you were there. In the world of deep submergence science, I want to begin a new field of research in deepwater archaeology. Just last year, I accepted a full professorship at my alma mater, the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island where I received my Ph.D. in the summer of 1974, just before going to sea on Project Famous. I am now director of the Institute for Archaeological Oceanography and starting next year we begin offering a dual degree with the University’s History Department. New graduate students in this program will receive a Ph.D. in Oceanography and a Masters in Marine Archaeology. Using our newly developed vehicle systems (Echo, Argus, Little Herc, and Hercules), we hope to pioneer this new field of research and uncover lost chapters of human history while the world looks on.