DIVER

Publish Date: June 2005

aquaCORPSE

Everything You Wanted to Know About The Making of The World’s Premier Tech Diving Magazine But Were Too Busy Waiting for the Next Issue To Ask.

“The best way to predict the future is to invent it,” read the quote (Alan Kay, Stanford Computer Forum) on the cover of the fourth issue of aquaCORPS. My initial vision for the magazine was to “invent” a forum for divers who were pushing the envelope to discuss what they were doing so that everyone could benefit from the information.

At the time, dives beyond 130 feet/40 meters were talked about in hushed whispers among hyperbaric intelligentsia lest the innocent be led to slaughter, and the mention of gas mixtures other than air evoked a perplexed look on the faces of the uninitiated, or worse— menacing stares from established quarters of the recreational dive industry. The real problem was that, what soon came to be known as “technical” or more simply “tech” diving, a name that aquaCORPS coined, was deep in the closet: no one was talking. (Read fear and trepidation), And all of us—the diving community—were worst off for the lack of exposure. The year was 1990.

Enter aquaCORPS—the spirited, take-no-prisoners magazine that I launched to address the then “taboo” subjects like mixed gas scuba, narcosis, over-pressurized cylinders, the bends, diving fatalities and diving to 500 feet on air (stupid then; stupid now) with all the seriousness and depth of a scientific journal, coupled with the in-your-face attitude and salty language of Outside magazine or the Rolling Stone. Wired magazine called it the “sea geek’s bible; part wish list, part chemistry book, and part looking glass.” And geek’s we were (think divers cranking out what-ifs on desktop decompression software running on shipboard laptops versus taking the PADI wheel for a spin—remember that?)

Over the ensuing decade technical diving became the tail that wagged the recreational dog, and former four-letter words like nitrox, the D-word (decompression), trimix, equivalent air depth, and rebreathers became an accepted part of sport diving vernacular. In a few short years, the operating depth of sport diving (including both recreational and technical diving) doubled from the maximum 130 fsw/40 msw recreational no-stop diving limit to 250-300 fsw/74-89 msw—divers were making their first decompression stop deeper than recreational divers were supposed to go. (Yes, a handful of tekkies went deeper, as they are wont to do but that was the practical limit for the majority). And the tech diving community was able to develop a set of training and operational safety standards, and the fatalities dropped.

Meanwhile, my Key West, Florida-based magazine grew from a 36 page, black-and-white, saddle-stitched book with spot color and no advertisements to a 100-page, full-color, perfect bound, ad-supported newsstand magazine after raising nearly a quarter-million dollars from investors-including the new publisher of DIVER magazine. We also added an annual tek.Conference, which grew out of the Enriched Air Nitrox workshop of 1992, along with EuroTek, AsiaTek and two rebreather forums, attended by sport, commercial and ,military dive aficionados from around planet. As a result, we were able to generate some solid ink in the likes of the New York Times, LA Times, Scientific American, Wired and Outside.

Heady stuff for a former Silicon-Valley computer nerd, but alas, user buzz and press clippings does not a business make. In hindsight aquaCORPS was never really a viable business, but instead more of a mission—and a personal one at that. I was the guy who was crazy enough, err, blessed, to be in right place at the right time with a team of enthusiastic supporters willing to try and pull it off. I like to think we put up the good fight. The truth is that we were the grateful recipients of at least one major miracle per issue—usually at the 11th hour and typically just enough to get the magazine printed, mostly paid for, and out the door. Unfortunately, we ended up growing faster than our balance sheet would support and it caught up with us.

Photo courtesy of aquaCORPS archive

Finally, after a six-year run, aquaCORPS’ bimonthly miracle failed to materialize, and issue #14, scheduled to run in February 1996, featuring cover girl Erica Leigh Haley, Canadian tekkie and co-leader of the TransPac Expedition, wearing only a toga and dive computer, never saw the light of day. (Alternatively, the universe deemed that we had paid whatever dues were owed and the miracle was my release from editorial servitude. I am still pondering this one). Within sixty-days, I was forced to lay off our entire staff and close the doors on the publication. Our attempts at resuscitation; raising more cash, selling the publication had failed. aquaCORPS was dead.

It’s been nearly nine years since I have penned a piece for aquaCORPS though I still receive a couple of emails each quarter requesting back copies of the magazine. PADI, a regular advertiser and sponsor of the tek.Conference and Rebreather Forums, launched its own tech diving program in 2001 which I took as a kind of karmic completion of our work and the ultimate vindication for tech diving which finally became mainstream. And so, it’s perhaps fitting that Diver publisher Phil Nuytten should now ask me to tell the story of to aquaCORPS and what really happened. Look for it in a coming issue of DIVER. In the meantime, I suggest that you keep your subscription current and plenty of oxygen on hand. You’ll be hearing from me—Michael Menduno/M2

aquaCORPS: The AUTOPSY

M2 on the Life and Death of a Unique Undersea Voice

In 1990 the dive industry’s hushed dialogue on the emerging field of technical diving abruptly became an out loud public debate. Metaphorically, ‘the gloves came off.’ Advocates and opponents gleefully argued the pros and cons of deep water, mixed gas diving for ‘everyman.’ The catalyst behind this sudden shift was a spirited young ‘tech’ (he coined the term) diver by the name of Michael Menduno and his brainchild, a brash, controversial and always opinionated magazine called aquaCORPS. Six years and 16 issues later, the flamboyant champion of countless ‘conventional’ scuba taboos, was gone, but its legacy lives on! Here is Part 1 of the story behind publisher Michael Menduno (M2 to his friends) and aquaCORPS, ‘the little magazine that could…and did!’

Michael Menduno in conversation with Phil Nuytten

Photo courtesy of aquaCORPS archive

What in your background convinced you of your ability to publish and edit a technical diving magazine, or, at least that you could quickly develop the ability to produce such a specialized periodical?

Ha! Blind faith and naiveté. I figured: how hard could it be? Blame it on my divorce and mid-life crisis. I was a self-employed marketing consultant in the computer industry in Silicon Valley and I needed a big change in my life. I decided I wanted to be a writer. And, in fact, I had been a writer all my life in one form or the other in my various jobs. I did my first interview when I was in kindergarten. No fooling. I interviewed a fellow classmate about his dreams of going to Mars and wrote it up in a picture book. I kid you not. I now think of it as the journalism gene. I find when I experience something amazing, or hear someone saying something incredible I get a burning desire to report on it and share it so others can be amazed, too. I also had the entrepreneurial fever. Heck, I lived in Silicon Valley. People were starting businesses every day. It seemed like the obvious thing to do. I liked reporting. I could talk to people. I could sell and I was a good organizer. Shades of Herman Hesse, “I can think. I can dive. And I can write.” Call it an exploration!

What led you to believe there was a need (and a commercial market) for a tech diving magazine? What was happening in the dive magazine field at the time you started aquaCORPS?

That’s easy. I was hungry for information and there was none—or at least it was hard to come by. I figured if I was so were a lot of other people. Whether there ever was a viable commercial market is debatable, but, oh, there was a need! At the time, Discover Diving and Scuba Times were around, and Skin Diver, of course; also, Florida Scuba News, California Diving News and Ocean Sport magazine. But none of them reported on the kinds of things some of us were doing. There was nothing being written about tech diving. It was pretty much a taboo, which, of course, made it all the more appealing to me.

Also, the whole thing made a lot of sense to me as a technologist. I felt diving was going through a technological revolution similar to what happened in the computer industry, a point that I made many times in my talks. Technology, whether computers, airplanes or diving gear typically begins with the help of government funding because they’ve got the money and also the mandate. Then corporations pick up on it and eventually advances trickle down to consumers. That’s what happened with diving technology; it began as a government purview, was picked up by the commercial diving industry and eventually knowledge found its way to those of us in the recreational field. It was similar in a way to the mix revolution in commercial diving that you helped pioneer in the sixties.

What did you see in tech diving that attracted you? Was it just that it was the top of the sport scuba ladder—as far as one could go—or something different?

Between the adventure of traveling on not-well traveled paths, the challenge of doing it, the technology and getting to dive in some amazing places, it was easy to fall in love with tech diving. Of course, there really wasn’t any tech diving, per se, at least not to the uninitiated, when I got certifiedinto it. At least that was very visible. It was very much in the closet although there were groups doing what came to be called tech diving: the wreckers like Gary Gentile and the Wahoo crowd and the cave diving community, but everyone kept to themselves. This kind of extreme recreational diving was not talked about in the general diving press. It was all underground.

My first exposure to this more rigorous diving came when I volunteered to participate in Dr. Bob Schiemeder’s Cordell Expedition in Northern California. It was 1987-88. I had moved back to California and had gotten back into diving, earning my PADI dive master ticket. That’s when I met Bob Schiemeder.

Bob and his crew were a group of Bay area geeks (engineer/scientist types that were in to marine sciences. I say that with affection. I’m a geeky kind of guy, too! The group was exploring sub sea pinnacles off the Big Sur coast and was looking for volunteers to help with marine surveys and to collect specimens. I bought a neoprene dry suit and rigged up a set of 72 cubic foot doubles with an amazingly unsafe manifold, made the check out dives and got accepted into Schiemeder’s group. That spring, I think it was in 1987, we made a series of 20-30 minute dives to 140-180 fsw/43-55m on air using U.S. Navy decompression tables. Schiemeder poo-pooed the use of dive computers, which were new at the time (I had one of the original Edge computers) and we didn’t even use oxygen for decompression! It’s hard to imagine now.

I was also going through a midlife crisis having divorced after 15 years of marriage and I was burned out from years in the computer industry. I moved to a tiny cottage on the beach in Santa Cruz and decided that I would become a writer. Not surprisingly I wanted to focus on my newfound love of diving and anything to do with the ocean. Ken Loyst at Discover Diving magazine gave me my first shot at article writing so I did a piece about the Cordell Expedition.

Photo courtesy of aquaCORPS archive

I knew this was going to be nostalgic. Indulge me for a minute. Here was my opening for that story, which ran in the Jan/Feb 1989 issue:

“And the sickness came. Again. And, again. Why God? I lay crumpled on the deck of the Cordell Explorer while the first team of divers worked to scoop up some mindless invertebrate 180 feet (55m) below the heaving swell and spray. It was different this time. The fear wasn’t there. Only resolve. I threw up twice. That was it. But my balance never returned – a casualty of that first onslaught of waves, BIG waves as we rounded Point Sur.

Sprawled on my back in a corner of the deck: dazed and confused. Restlessly dreaming of whales and a woman I once knew biblically, alone with the glaring sun overhead turned indifferent. And the rising, falling, rising, falling bleached white deck against the blue. That blue. To the newly initiated volunteer (and practically everyone else), ‘ocean science’ can be a very humbling experience.”

That was my opening salvo.

I don’t think Loyst was prepared for what he got. Between using the f-word, the d-word (decompression), references to Jim Hendrix solos, comparisons between narcosis and psychedelics and discussions about dives that were simply not allowed by the recreational diving community at the time, we had a heck of time editing the article for print. The piece was literally filled with warnings and disclaimers. Remember, at that time (before aquaCORPS), a lot of dive magazines tended to sport commercial, kissy-face family sort of content. Not that there was anything wrong with that, but there were other perspectives.

Fortunately, Ken’s publication was more on the edge than most. I still have a copy of the $100 cheque I got for the article. I went on to do a series on diving technology and travel for Discover Diving. I also wrote some profiles on guys like Richard Nordstrom who was then president of Orca (dive computers), and photographer extraordinaire Marty Snyderman for the magazine. That was the start of my professional writing career.

What was the aquaCORPS mandate, in your mind? Did you have a formal mission statement? How did you convey to staff and readers your objectives?

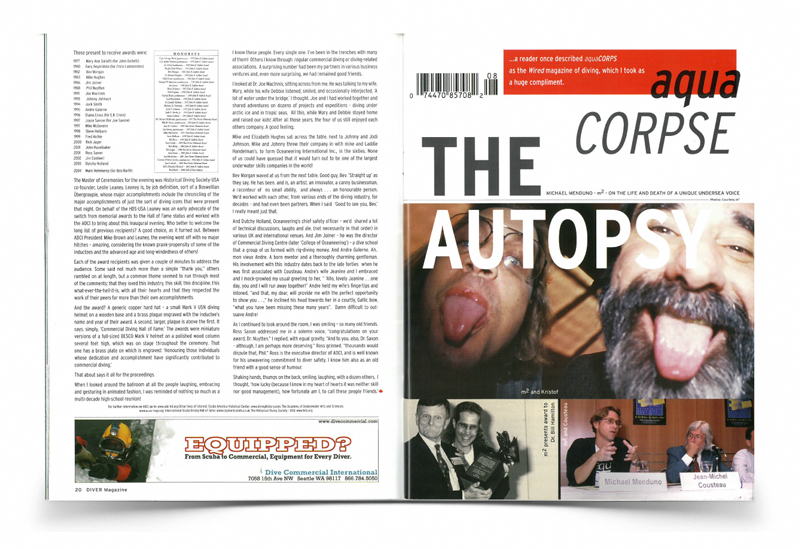

Overall myour mission was to provide a trove of deep, rich accurate information about the technology, practice and culture of diving—a kind of ‘Rolling Stone’ or ‘Wired’ magazine of diving, if you will. In fact, a reader once described aquaCORPS as the Wired magazine of diving, which I took as a huge compliment. It was also to serve as a forum for this diverse, eclectic group whose interests were focused on the underwater world.

That my our mission statement’s top priority was not focused on building a profitable business was likely one reason that the business never became profitable and eventually had to close its doors. For me aquaCORPS was more of a cause or a mission than a business. It was never really about making money. But then I am more of an artist/writer/creator in temperament than a merchant.

Conversely though, now that I think about it, aquaCORPS probably lasted as long as it did because it was more of a mission than a business. I was not doing it for personal profit; hell, I didn’t even draw a salary for most of my aquaCORPS years. I was living hand to mouth and perversely I think this opened the door for people to help. In many ways aquaCORPS and tek was a community effort. And I was a bit of a pied piper.

I always felt that aquaCORPS was a gift to me from the universe. And I felt blessed to have been the right person at the right time with the right set of skills to nudge the wheels of diving history in some small way and have an impact. It was heady stuff.

Photo courtesy of aquaCORPS archive

Back up a minute and tell me about your early diving influences and your start in diving?

I was a huge Cousteau and Lloyd Bridges (Sea Hunt) fan when I was young, and always fascinated by the ocean. There was also Jules Verne and another TV series about a futuristic sub that roamed the world’s oceans. I used to have a recurring dream that the ocean waters suddenly drained away and I was walking along the ocean floor seeing all kinds of amazing creatures and plant life.

I learned to dive in 1976 while in grad school at Stanford University. I was 24 at the time and had moved to California from the Midwest. My first open water dive was at Lover’s Point in Pacific Grove, California, after watching the movie Jaws, which had just opened the night before. The music (boom..boom..boom..boom) and the image of those big jaws definitely kept me on my toes that first dive. Yowsers! Six months later, I transferred to Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, part of Stanford University, where I started taking marine biology courses and got involved in scientific diving, around 1977-78.

I soon discovered the divers at Hopkins and those at the local dive shop were in two completely separate worlds with no contact between each other. It was ironic and seemed a shame to me as a member of both groups so I organized a weekend dive workshop open to everyone. It was a chance to get together and I arranged to have divers from Hopkins and the local dive community to give talks. We also made some dives together. I guess you could say that it was foreshadowing for aquaCORPS and the tTek Conference in the movie of my life.

A couple of years later, I finished school and moved to Washington, DC, to work as a senate staffer for U.S. Senator Ted Stevens from Alaska. This took me away from diving until the mid 1980s when I returned to California to work in Silicon Valley as a techie…the computer kind that is.

So, then, how did you learn tech diving?

Well, that was one of the great benefits of aquaCORPS. I got to train with some of the best divers on the planet. I started by training with Bob Scheimder and his folks. Then I went to Florida and then Mexico to complete my cavern and cave diving training and then started going to Key West to train with Capt. Billy Deans and learn mix diving. I subsequently moved to Key West to be closer to the action and joined Billy’s staff. We worked to create the first tech diving (nitrox, trimix) training courses. Tech diving was all about learning and training and perfecting and pushing the art, and Billy’s shop, Key West Diver, (only a couple of miles from the aquaCORPS offices) was a meccaMecca for tech training; it was the place to be.

I trained with Lalo Fiorelli and Steve Gerrard for my full cave diving certification, and participated in some of Steve’s Yucatan expeditions. I also got to dive with and learn from some amazing divers like Sheck Exley, Gary Gentile, Jim King, Wings Stocks, Rich Pyle, Paul Heinrith, John Crea, Chris Sorauf, Dustin Clesi, Bob Raimo, Tom Mount, Bret Gilliam, Mike Madden, Gary Walten, Eric Hutchinson, Kevin Gurr, Rob Palmer, Karl Shreeves, Hal Watts, Ed Betts, Jim Brown and Joel Silverstein. Sooner or later everyone showed up in Key Westthere. From that point of view I had a great job!

What kind of gear did you use? Plain vanilla, but tekkie? Or nitrox, or He02? Were rebreathers ‘in’ then or just over the horizon?

I was diving with recreational gear; single tank, BCD, dive computer etc., until I got into cave diving and deep diving. Our standard rig at Key West Diver were double hundreds or better as far as tanks, a back-mounted wings-style BCD with a redundant bladder, Poseidon Odin regulators, stage bottles of course, depending on the dive, typically one EAN cylinder and one O2 cylinder, DUI crushed neoprene dry suit, a Beuchat dive computer which I used as a depth gauge, (this was before everyone came out with mix computers), DCAP tables courtesy of Dr. Bill Hamilton, Force Fins, a jon line, reels, dual lights, I used Lamar English lights, a writing slate and a life bag and emergency ascent line. For open water dives we also carried an emergency kit with flares and a satellite transponder. And for transportation, we used aquaZepp scooters. Rebreathers were really available yet and we had several at the shop at different times but outside of a few trail demos I never dived one.

What did you do, mostly? Just look, or snap pictures, or poke fish, or explore caves … or just enjoy pushing the envelope?

Again, I just loved being underwater in any way shape or form. I was enthralled with the underwater environment. I enjoyed more challenging dives because doing them right took work. That’s part of the whole tech thing, I think. Putting it all together, planning it out and then executing the plan. It was also amazing to me to see and experience some of the places one can go underwater: I’m thinking about being an hour deep into some unearthly underwater cave—better yet a virgin cave!—or floating through a sponge-encrusted tunnel that opens out on a wall at 140 feet (43m) in Cozumel (on air! (I always loved that nitrogen buzz, though mix is the only way to go for deep stuff).

OK, so you get the idea for a technical diving magazine – how did the plan evolve? Who were some of the people involved editorially, with the writing, initially? Can you identify the staff for the first issue or first couple of issues? Where were you located while all of this was going on?

I was living in Santa Cruz, California, at the time. I knew a couple of freelance editors from my work as a freelance writer. My lover was a graphic designer. And there were a lot of people with stories that needed telling. So I just started cobbling the magazine together. The original staff was me, my editor, Susan Watrous, who I had a huge crush on at the time, graphic artists Davina Midori and Pam Falke. I also got lots of help, encouragement and support from friends in the computer business and people in the diving industry like Dr. Bill Hamilton, Marty Snyderman, Steve Gerrard, Wings Stocks and others.

The magazine really began to take off two years later when I moved to Florida and started organizing the first Enriched Air Nitrox workshop with the help of Dick Long, founder and CEO of DUI, in response to the so-called ‘nitrox controversy.’ And I made several friends/supporters/mentors who hung with me for the rest of the amazing journey that was aquaCORPS. They were Lad Handelman, the former CEO of Cal-Dive and Oceaneering, who joined the aquaCORPS board; sport diving industry veteran, Bill Roe, with Florida Scuba News; and Billy Deans who I already mentioned.

aquaCORPS and the tek Conference would never have lasted as long as they did without the personal help of those three people. But three are in a class by themselves. There were many others whose help made the magazine and conference: people like dive physiologist Dr. Bill Hamilton, for example. Bill played a huge role in the development of aquaCORPS and tech diving and gave us intellectual credibility and tables. And Mr. Rebreather, Tracy Robinette, a voice of realism and sanity was enormous help to aquaCORPS and to tech diving. There were also some key staff people who made a huge difference: Mike Belininski, aquaCORPS’s main graphic designer and Mac guru (aquaCORPS would have embolised early on without Belinski)), and Julie Pounder, who represented the magazine in the U.K. and was always there to help, and writer Walter Comper, who helped organize the tek Conference and represented aquaCORPS in Europe, and our office manager in Key West, Smokey Parrow.

So . . . the magazine is ready to rock ‘n roll – how did you finance it? Right from the first it was a high quality, expensive magazine to produce. Did you float the first issue(s) out of your own resources? Friends? Relatives, or what?

As I mentioned at the outset, I’d just gone through a (very painful) divorce and that, along with the collapse of my Silicon Valley consulting business, had left me with virtually no resources so, unfortunately, there weren’t many alternatives. I had to raise money. So here’s a story for you. Because I needed money to get the publication off the ground and didn’t have any I took the approach that my mentor Lad Handelman later codified for me. He had once told me that if I just pretend and act as if it is going to happen no matter what, then it will (happen). I figured (naively, I might add) that if I just got the first issue out the rest would take care of themselves. So I took that approach and just knew in my soul that it was going to happen, that I would make it happen no matter what.

And so I had a few hundred dollars to get going, and convinced my team of contractors that we would have the money and they would get paid. And I convinced the printer that they would be paid and managed to get them started without a deposit. And I managed to scrape up enough money for my DEMA booth for the January 1990 show where I planned to launch the magazine. We began working on aquaCORPS issue #1 the previous October. In the meantime, I was madly calling all my business associates and friends and relatives to raise seed capital to put out that first issue.

By early January I had the issue edited, layout done and it was shipped to the printer who was to produce 2,500 copies and have them ready for me to pick up Wednesday morning so I could board the plane in the afternoon for Orlando, Florida and the DEMA show.

The only hitch was they wanted a cheque for $7,500 and I had something like $200 in the bank. That very same Wednesday at 10 a.m., after two months of fund raising efforts, my first investor, a entrepreneur named Adam Albright, who lived back east, told me he would wire $10,000 later in the day. There would not have been an aquaCORPS without Adam at least not in time for DEMA 1990!

I drove to the printer. Wrote them a cheque for $7,500, picked up the boxes of magazines and headed for the airport. The scary thing was, believing that I could ‘make it happen,’ I’d already decided that I would write the cheque for $7,500 whether or not Albright came through.

Truth is I had to write several big cheques with no money to cover them on several occasions during my aquaCORPS stint. I figured I could always raise the money or negotiate my way out of the problem after the fact. I’m not proud of that; it was illegal and a very stressful thing to do. You could say that I was driven and determined, really stupid, or just had a lot of faith. Probably all of them were true. Unfortunately, aquaCORPS never got easy. I needed at least one major miracle to happen each issue and it did for six years and 16 some issues if I include my TechDiver publication as well. And then in February or March of 1996, the run of miracles ended and I was forced to close aquaCORPS.

How about outside investors? Was that in the mix from the start, or just a “we need an angel” move, later?

I always wanted to put aquaCORPS on a solid business footing. Trouble was I was not really a businessman at heart. I don’t think a true numbers crunching businessperson would ever have launched aquaCORPS in the first place. In retrospect, there wasn’t a large enough market to make it a profitable, sustainable business at the level I envisioned. Of course, I didn’t realize that at the time. Ken Loyst once told me I should have kept aquaCORPS a small, quarterly black and white newsletter and from there build it much more slowly. He was probably right in some way and had I taken his advice, aquaCORPS might still be around. But that was not our path.

As I said it was more of a personal mission or cause than a business. I managed to get a few angel investors from among friends and family. Eventually, with Laddie’s help I was able to get some outside investors led by Rod Stanley, CEO of American Oilfield Divers. (aquaCORPS would have sank in 1994, right after the “C2” issue #7 if Rod & company hadn’t of stepped in). You were part of that Phil and I really appreciated your investment and having you on board! You remain one of my heroes!.

I was totally excited about securing a sizeable investment even though it meant I had to give up control of the company in exchange for the funding. I believed that this cash infusion would help make aquaCORPS a successful business and that’s what I wanted. But the reality was I needed help running the business as much, or more, than I needed money! I was heading up the design, editorial and production of the magazine, spearheading conference planning and trying to run the company. The workload was sufficient for two full time people. I was in over my head and never really able to get all the day-to-day help that I needed. In retrospect though, it may (or may not) have made a difference.

Laddie later told me that I should have sold the business in 1995, the year that tech diving and aquaCORPS seemed to peak. It was great advise but just then I was up to my eyeballs, no, scratch that, I was way over my head trying to keep the company afloat, to manage about 10 employees, put out aquaCORPS on a more frequent basis and organize the tekConference. It was a 24/7 job for way too many years. I gained a new respect for business management. I learned the hard way that being good with people, motivating, organizing and instigating, and being a great creative director, was not enough. I was not a good business manager. It’s a real skill.

In the conclusion of this exclusive Diver Magazine AquaCORPS interview, publisher Michael Menduno talks about the controversial ‘nipple’ and ‘manipplelator’ illustrations, the infamous Bondage pictorial, the highly regarded AquaCORPS tekConferences and in the aftermath of it all, what m2 is up to these days.

End Part I

aquaCORPS: the AUTOPSY

Part II

Magazine with ‘Attitude,’ reveals Naked Truth to Divers

Arguably it was the most controversial magazine in diving. Founded on “blind faith and naivete´,” according to publisher Michael Menduno, aquaCORPS gave voice to technical diving at a time (in the early 1990s) when prevailing industry opinion argued that deep water, mixed gas training for recreational divers would be to lead the lambs to slaughter.

Part I (Diver June 2005) of this interview looks back on that time, tracing Menduno’s (known as M2) personal journey through training and the realization that there was an urgent need to share accurate information, not withhold it, in the face of growing interest and demand. In this concluding segment M2 retraces the brief glory days of aquaCORPS, ‘cheeky’ as ever and in its own inimitable style, giving new meaning to technical diving as a ‘discipline.’

Michael Menduno in conversation with Phil Nuytten

Photo courtesy of aquaCORPS archive

During the early days of aquaCORPS, it seemed like there were exciting things going on in the tech diving field almost every day. Guys like Sheck were doing their thing and companies that catered exclusively to tech divers were starting up. What about people like Sheck and Billy Deans and Richard Pyle and so on, people whose ‘doin’s’ were central to the magazine, were these guys friends or just interesting people to write about? I guess I’m asking if you felt your role was to chronicle what others were doing, or if you were a part of the doing?

Well, I certainly felt like a chronicler. I love telling people’s stories. And what amazing stories they were. That’s what aquaCORPS was all about: people’s storiesthe story of people-EXPLORERS-driving a technological revolution. But I was reporting on my friends in a lot of cases. I lived at Billy Deans house for my first three months in Key West and put out aquaCORPS from his living room and dive shop. We were close friends. There were so many people I admired and just found fascinating. Many became friends. You mentioned Sheck and Rich Pyle. Both I regarded both were of them as friends. Rich Pyle still is. [Sheck Exley died while cave diving in Mexico in 1994] And of course there were many others who touched my life and that of the magazine. There was you. And others: Carlos Eyles, Steve Gerrard, Tracy Robinette, Bill Hamilton, Wings Stocks, Walter Comper, Joel Silverstein, Brian Skerry, Mike Wehrs, Barry Brisco, Emory Kristof, Drew Richardson, Karl Shreeves, Wes Skiles, Jim King, Jim Bowden, Richard Stewart, Lamar Hires, Hal Watts, Ed Betts, Tom Mount, Erika Haley, Simon and Polly Tapson, Gary Gentile, John Chatterton, Bobby Delise. The list goes on and on. I like to think I have/aquaCORPS had a big list of friends and supporters. As you’d suspect, some of these people became close personal friends some were more business associates. I think people and their motivations are a lot of what made tech diving so fascinating and made it a compelling subject from a journalistic point of view. I am still fascinated by the peopleexplorers and what made makes them tick.

Scuba Forums were just starting on the net, then, and aquaCORPS was one of the major topics in the tech section; very homey/nerdy kind of discourse: “I just got my issue, did you get yours yet?” And there were endless discussions on the magazine’s content. Were you or your people aware of these Forums? Follow them? Did they affect any of your content?

Online forums were just starting up. Yeah, we would scan them for comments and ideas. I also talked to dozens of divers and industry people every week and that certainly ended up influencing what was in the magazine.

And, speaking of content, walk us through the famous ‘nipple’ and ‘manipplelator’ illustration. It was in the ‘Hard’ issue, I believe. Boy, there was a lot of heat over that one! In fact, the artist’s illustrations in that whole issue seemed to offend some number of readers – a few? A lot?

I know people really got crazy over that one. I suppose it was kind of juvenile, ererr testosterone-esque to run it. That one came out of my trip to Vancouver and dives in the Newtsuit. Man was that a blast. I remember suiting up and joking with IANTD instructor trainer Ericka Haley, who I and everyone else had a crush on. We were joking about the Newtsuit and how sensitive the manipulators were and I think I jokingly reached out the manipulator arm towards her chestbreast. Well you get the idea. When I got back to Florida I found this great artist who drew this futuristic hard suit and, well, the pincher and the tit illustration sort of just came into being. My idea was to have kind of a ‘zine’ of edgy art within the larger magazine. I took shit from my staff for running it.

I should say that the next art spread—the dominatrix and combat swimmer chained to the oxygen cylinders in the Wreckers issue (#9) also drew some controversy. Caption: “Wanna Get Into The Loop? You need diving discipline. (It’s more than just a card!). Nitrox training. Plenty of Bottom Time. Call today and dive as deep as you deserve.”

In fact, that issue was banned from The Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) in Panama City. Apparently the female CO was offended. Controversy is usually good for publications – it increases demand and we wanted to have some fun and break the mold. Interestingly, our dominatrix BDSM spread ended up in an art gallery in Key West. I guess you could say that we were exploring cultural themes along with diving. Face it, strapping doubles and sidemounts on your body and clipping yourself to an aquaZEPP is definitely a kind of bondage experience.

The follow-up issue with the ‘Bondage’ picture in it seemed to some readers to be a “this is my magazine and I’ll print whatever in the hell I want!” sort of statement from you. Was it?

Well, there were some elements of that. I actually thought that the bondage issue was in better taste then the pincher and the tit, which I now think is was sexist and probablyno doubt was offensive to many women and men. . I [probably] wouldn’t run it if I had it to over. However, the bondage spread was funny and made a point. Perhaps it was just too hot to handle. I guess part of what we discovered is that the diving community is quite culturally conservative overall. Funny, huh. People could dive to hundreds of feet down, miles back in some underwater cave, but run some provocative art and they flip out.

Leave the magazine for a moment. What about AquaTek aquaCORPS’ tek– theC conferences? They were highly regarded by the entire diving industry, not just the Tekkies. How did the idea of a physical tTech fForum come about? Who were the people involved? Were these conferences funded from aquaCORPS revenues or other sources? Would you talk about the structure of the conference, in some detail? Were they risky to stage? Were they moneymakers?

The tekConference evolved out of the Enriched Air Nitrox workshop that we organized in 1992 in response to the controversy over nitrox. Bob Gray at DEMA had banned IANTD and ANDI and the other nitrox people from exhibiting at the January 1992 DEMA show. (The ban was later rescinded). We stepped in to organize a two-day forum to get industry members together to discuss the issue of nitrox and mix. The idea of doing a conference each year in conjunction with DEMA just followed naturally. My idea was to bring the magazine to life in a conference style format. And it worked! We funded the conference from aquaCORPS’s cash flow, which was pretty slim. We sold booths and sponsorships and attendees and split training class fees with instructors.

Laddie helped me to organize that first tekConference in 1993. I was living in Key West at the time. The phone company pulled the phone from my home/office when I couldn’t pay the bill. I borrowed a calling card from a friend and ended up organizing the conference using the corner telephone at a little Cuban grocery store called Five Brothers Grocery. [I have a picture of this!!] I spent mornings making calls then would jump on my bike and peddle three or four miles ( m) to Billy Dean’s dive shop where I would enter stuff into the computer etc. I never let diving poverty stop me.

Sometimes it felt that aquaCORPS was a kind of cross that I had to bare, or chose to bare. I was going through a good deal of pain in my family life and so I think I poured myself into aquaCORPS in part to escape some of that pain. Not a healthy thing to do necessarily but that was my way of coping at the time. I’m not sure I was even conscious of it entirely. Of course, running aquaCORPS with hardly any money was itself stressful and painful, but also very rewarding.

I can see there would be some solid (potential) synergy with conference presenters and exhibitors as magazine subject material and advertisers. Was this part of the plan or just something that evolved?

It was an evolving plan and it just seemed to make a lot of sense. Like aquaCORPS though, the problem was always getting enough ENOUGH buyers, attendees, subscribers to make it profitable.

At the AquaTek tekCconferences it seemed like you were everywhere, doing everything, and looking like you hadn’t slept in days! In fact, it looked like only adrenalin and your recreational chemicals (I mean, like coffee, ovaltine, Gatorade, etc.!) were keeping you goin’! Comment?

Man, they were like running a triathlon. Five days of minimal sleep, maximum stress, a ton of work. Part of the problem was always lack of money, which meant we had to work a lot harder to get things done and I could never really pay people adequately. Fortunately it was a community effort and so I had a lot of volunteer help. along with the recreational chemicals. God bless Ovaltine! It sort of balanced out the 24/7 craziness. I have a lot healthier lifestyle today! Outside of nitrox and trimix, I tended to be abusive with my recreational chemicals. It was an offshoot of the 24/7 craziness that was aquaCORPS. The truth is that I didn’t take very good care of myself during my aquaCORPS years. Fortunately that’s changed. I am a lot more loving to myself and have a much healthier lifestyle.

Consensus seems to be that everybody loved the magazine but were annoyed when issues got later and later. Was that because of a lack of material? Lack of funds? Problems between you and staff? Or, all the above? Or something else?

Funds were always a huge problem and so was staffing. Let me just say that most people don’t move to the Keys to put in sixty hour weeks and work their asses off. And as I mentioned, I was not the best manager. It was my cross to bear for many years. I mean I was happy that people couldn’t get enough of the magazine but it was painful that we could never get them out fast enough. Let me tell you, I tried.

You’ve said that you had to shut the magazine down when, one month, an ‘angel’ didn’t appear. Sounds like the magazine had been on thin ice for some time or was it dicey right from the start?

As you have probably gathered by now aquaCORPS was pure vegematics-ville as far as dicey and it really never varied from that except for a brief period after we received our first $100,000 investment. Normally, a major miracle or two was needed to put out each issue. From a business point of view it should never have been like that but then, as we discussed, I‘m not sure that it ever was a viable business. Still, it was something that needed to be done. And, perhaps, like a lot of tech diving it took some crazy, obsessed people to do it. I fit that bill. I lived pretty much on nothing for the seven years that I worked at aquaCORPS though I had great diving gear, got to travel to exotic places, met fascinating people, made a lot of fabulous dives and got to be a part of history. Hard to beat that. I wouldn’t trade the my aquaCORPS experiences for anything.

Photo courtesy of aquaCORPS archive

Must have been tough to shut down aquaCORPS when there seemed to be a real demand for it – or were you just tired?

It was heart-breaking breaking, Phil. It felt like my world was dying. I was sick about it. We just barely pulled off the tekConference in January of 1996 and came back to key West to finish the next issue (#13) which was to feature wreck diver/explorer Erika Haley on the cover wearing a toga and a dive computer. [Note that aqauCORPS published 12 issues of aquaCORPS Journal and four issues of techDiver.] But when we got back from the conference it became clear that something had radically shifted. Our funds were way down from having put on the conference and ad sales were slow. The company slowly ground to a halt over the next two months. It was agonizing. Like watching a collision or a ship sinking in slow motion.

I tried frantically to reverse this course, raise more money, and/or sell the company without success. I talked to investors. I flew out to California and pitched John Cronin and the PADI executive team on buying aquaCORPS. All these efforts were without success. A month later, I made our last payroll, realized that it was going to be impossible to make the next and was forced to let everyone go and close the office. I hadn’t given up but I thought if I could temporarily cut expenses drastically I might be able to sell or salvage aquaCORPS.

I moved the company into my living room. I called everyone who could possibly help. There were a couple of people who expressed interest in buying aquaCORPS. I flew to Pittsburgh and made a presentation to a wealthy entrepreneur/diver/business owner. He was interested but his lawyers were dead set against it. I tried other publications like Asian Diver. By July I realized that it was over. I felt horrible but at the same time there was an amazing sense of relief that the torture was over. A month later, a truck belonging to my largest investor pulled up at my house and we loaded all the computers, inventory and remaining office furniture, and the truck drove off. I had long ago put all of my resources into aquaCORPS. I was left with a few clothes, a bicycle and a MAC SE computer. It was sobering.

How big was the subscription list? How many copies were printed per issue, on average? Did you try to sell the magazine?

That was one of the problems. We never really knew. We had a Rube Goldberg subscription system that required a degree in rocket science to operate. Why we didn’t just go out and buy a database I don’t know. Hindsight is 20-20. I can tell you that we were printing 40,000 copies at the end and we worked to sell and/or give away every issue that we could. I figured if people read aquaCORPS they would buy it. We might have had 5000-7500 regular subscribers and the rest went to retail dive stores and newsstand distribution.

aquaCORPS shut down some nine years ago? What happened after that? What did you do for the next few years?

My immediate plan was to stay in the diving business. I put on AsiaTek with Rainer Sigel at Asian Diver. I organized the Rebreather workshop 2.0 with the help of Drew Richardson and Karl Shreeves at PADI. I wrote a tech column for PADI Undersea Journal. I pitched a couple of book ideas to Best Publishing and others. I did a lot of soul searching trying to cope with my loss and figure out what the heck I was going to do.

Then, in 1997, I decided to move to Spokane, Washington, to volunteer to help put on an international conference for a spiritual organization called Subud that I had belonged to for many years. I thought the change would be good for me and at the time I had no idea what I wanted to do next. I organized and produced all the printed materials for the conference and ran a daily conference newspaper for the two weeks of the event. That finished in August 1997. Following the conference, I packed a rental car with all my belongings and drove back to my home town of Chicago. I arrived with $100 in my pocket. My mom and step dad gave me a ton of shit. “How can you be 45 years old and not have a job or a penny to your name?” Well ma…it’s a long story.

I went to live with an old friend who was kind enough to let me sleep on his living room floor, and I began looking for a job as an editor. The magazines I contacted were either not hiring or at least not hiring me. However, several suggested that I consider writing freelance articles for them. I landed my first freelance writing gig writing for Crane’s Chicago Business. It was October 1997. I decided that to return to freelance writing and was quickly able to parlay my experience and contacts into writing assignments for Wired and Scientific American, both of which had written about me and aquaCORPS. I moved back to Santa Cruz, California, about six months later and began my freelance writing career. I then moved to Silicon Valley, the heart of the tech world, to be closer to the action. I started writing for technology and business magazines. I was back in Silicon Valley.

Tell us what you’ve been up to for the past few years?

I moved from Silicon Valley to Palm Springs, California, in 2001 and got married a year later to a wonderful woman named Deborah. Deb’s a culinary artist and works as an executive pastry chef for a high-end restaurant group here in the desert.

I decided to go back to my childhood love of music (I played electric bass in a variety of rock’n’roll bands from age 12 to 22). I got back into music when I moved to the desert. I have been studying and taking online classes at Berklee College of Music and now play in a number of bands. I have a 60s sixties rock and pop band called Radio 60, a harder classic rock band call the Instigators and I also play with a surf music band called The Woody’s and a jazz band in the making called ‘Freeway Jam.’ I play gig two to three nights a week between with the various bands. My goal is to be a jazz musician.

Funny, gigging is not unlike the diving world: a small team of people team to explore an uncharted (musical) environment. It definitely requires an “operational” approach. Music is also pretty gear intensive. I go on stage with $4000-5,000 of gear supporting me not unlike a tech diver going in the water. Once a gear junkie always a gear junkie. And of course, there are those musicians that swear by special mix. I digress.

Last year I organized a three-day educational workshop for bass players in Tempe, Arizona, called under the moniker ‘The School of Bass.’ Shades of the rebreather forum. We had about 40 some attendees and some big names in the bass world. The event was sponsored by Fender Musical Instrument Company, Carvin, Bass Player magazine, La Bella strings, Hal Leonard Publications and The Bass Place. My thought at the time was that maybe I could start a business conducting educational music workshops (with me as the ‘head student’) and maybe even publish a newsletter. I pulled off the workshop. I lost a few grand on this first event, but from a content perspective it was incredibly successful. Attendees rated it a 4.75 out of 5. There was interest in doing more. I had support and encouragement to do another workshop but after a lot of soul searching I decided not to go the aquaCORPS route. I realized that I want to be a great bass player, not have a great music workshop business so I decided not to do another workshop for the time being and instead devote my time to playing. I try to practice/play at least four hours a day. I am having a ball!I have matured and am a lot healthier and self-loving these days.

As far as mya day job goes, I work from my home for the research subsidiary of an institutional brokerage firm, called Off The Record Research, based in San Francisco, and make about the same money as I did as a fulltime freelance writer. Essentially, I conduct freelance investment research on technology companies. Also I write the occasional freelance article for Wired, Bass Player and a few dive magazines like Undercurrent.

Do you currently have any contact with the people from the aquaCORPS days?

Oh yeah. I have a lot of friends all over the world and we keep in touch. I also get a letter or email about once a quarter looking for back issues of aquaCORPS.

What would you say were aquaCORPS’ main accomplishments/contributions? Anything most proud of?

I think aquaCORPS accomplished a great deal. There are a lot of things I’m really proud of. I am pleased that I/wewe were really able to bring all the various dive communities;, i.e. sportthe recreational establishment, the cavers, the wreckers, commercial divers, scientific divers and military communitiesthe military together, and provideing a bridge and forum for them to communicate and share what they knew with each other.; I think that was a unique contribution and I am very proud of thatit. The fact that parties from all persuasions and viewpoints were able to come together at aquaauCORPS and the tek.Conference was very rewarding, and when you think about it pretty amazing given the highly independent and sometimes cantankerous nature of divers! .

I am proud of the magazine itself, I think it raised the bar for dive publications both it terms of design and editorial content. Hey, we were the first dive magazine in which interviewees could say “fuck” and not be censored and we didn’t pull any punches or dumb down the technical material so that the masses would get it. Wired magazine called it the “Sea geek’s Bible.” I quote from one of their reviews, “For vacation divers like me, aquaCORPS is part wish list, part chemistry book, and part looking glass. But for technical and hardcore sports divers who live to dive and dive to live, aquaCORPS is as essential as oxygen.” Heady stuff. I think that we were also very successful in telling the story of diving, and tech diving to the world at large. aquaCORPS and the tekConference was written about in Scientific American, Outside, The New York Times, LA Times, Wired and that was very cool.

aquaCORPS and tek were also really a very strong force for improving both diving performance and safety. As my friend Billy Dean says, “we doubled our recreational playground.” Before the tech revolution sport divers were pretty much limited to about 130 fsw/40 msw. Now you could say sport diving range extends to 250 fsw/75 msw or so. Diving beyond 250 fsw is another ballgame. aquaCORPS was also a stickler for safety and we took a lot of heat at times for sticking with that position. I’d like to think we made a difference and saved some lives.

And as I’ve said, I feel lucky and blessed to have been able to witness, and in some way help facilitate, some would say foment, a technological revolution. How often does one get to a part of something like that? I was in in the right place at the right time to recognize what was going on, and to give tech diving a name and a voice and to make people aware of it. I feel very grateful for that privilege.

Any regrets over the whole enchildaenchilada?

None at all. Of course, I would probably do things very different today but that’s the benefit of hindsight and experience. I certainly made mistakes publishing aquaCORPS and did some embarrassing things but I can honestly say I did the best I could in the circumstances and with the resources at hand. I’m proud of aquaCORPS and what we were able to accomplish.

Any advice for an aspiring dive magazine publisher?

Wow. Find and focus on your unique voice. Don’t try to follow others and don’t pull any punches. Create a magazine that you want to read, that challenges you, and that lifts you up. Tell people’s stories, the real stories. Tell the truth. And get your funding secured early on and sell a shit load of advertising.

What about your diving?

As you might suspect, I got burned out a bit after aquaCORPS. That passed but I haven’t been diving for a number of years. I do miss being underwater though. I have often thought that when I get back into diving again I am going to start by learning to dive a rebreather. I can actually afford one now. Unless, of course, you have your swimmable EXO suit ready by then.

As our Governator (Arnold Schwarzenegger) said, “I’ll be back!”

We’ll be waiting. Thank you, Michael.

Thank you Phil for all your help and support!