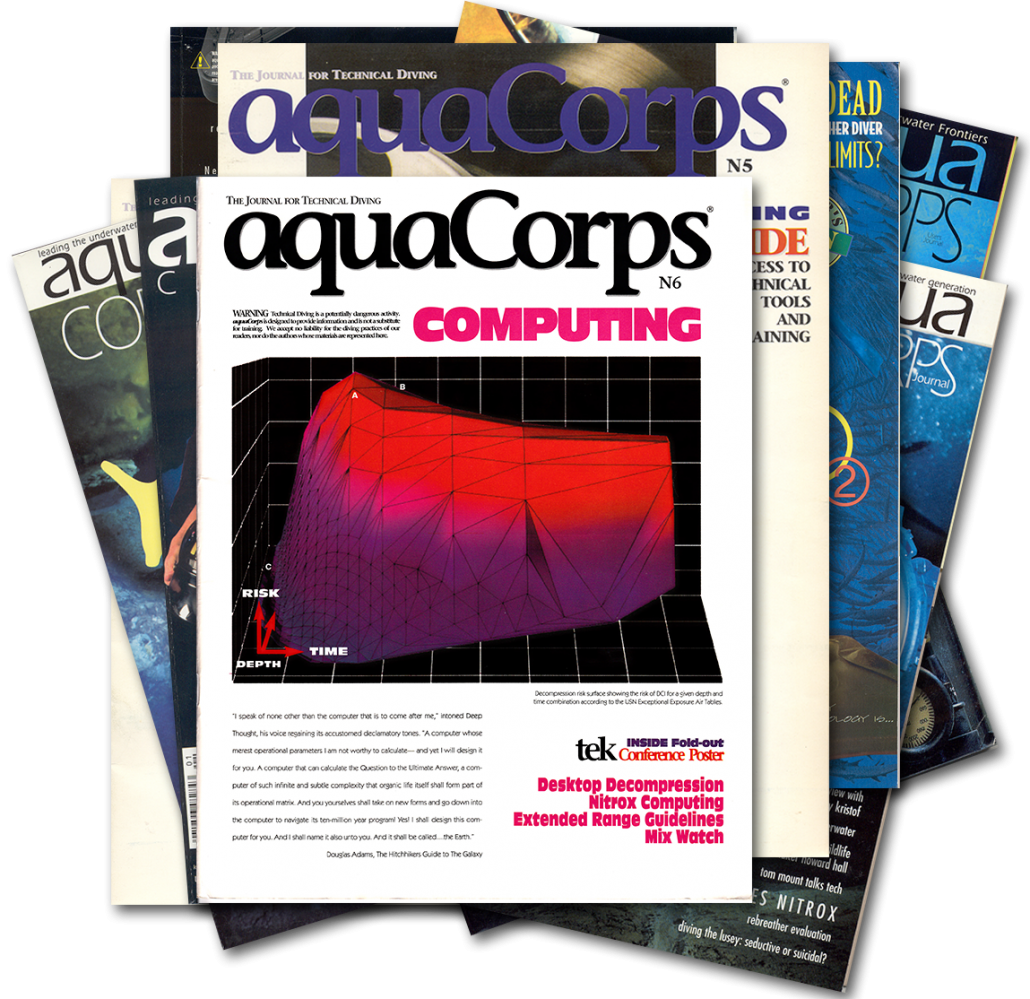

Journal #6

Computing

Publish Date: June 1993

Reprogramming The Future: An Interview With Kevin Gurr

Prologue:

Kevin Gurr has been passionate about computing and rebreathers since his first rebreather dive in 1987. The prolific 58-year old British explorer, tech instructor and engineer got his start rebuilding the electronics for the BioMarine CCR155—one of the first mixed gas rebreathers to be adopted by sports diving divers—and went on to build the first nitrox dive computer, the ACE Profile, in 1991 before most divers could even spell N-I-T-R-O-X. He sold several hundred units and planned to add a data logger, gas sensor, on-board analyzer and “look-ahead” capability, but the project got shut down for lack of funding. Two years later he released Pro Planner desktop decompression software to address the needs of the emerging technical diving market.

In 1997, Gurr rolled out the world’s first mixed gas diving computer, the VR3, which he manufactured and distributed through his newly formed company VR Technology Ltd. based in Dorset, UK. The VR3, which was capable of handling multiple nitrox, trimix and heliox mixes was also the first computer that supported closed circuit rebreather (CCR) diving, and later, the first to run the popular Varying Permeability Model (VPM)—the decompression model behind “deep stops” [Now deemed inappropriate]. As a result, The VR3 quickly became the computer of choice among technical divers and remained so for more than a decade.

But Gurr, who mentored with rebreather pioneer Dr. Bill Stone in the 1990s, wanted to build his own rebreather. In 2005, VR launched the Ouroboros closed circuit rebreather, aka “Boris.” Three years later they rolled out the Sentinel, the first CCR to incorporate a gaseous carbon dioxide (CO2) sensor capable of detecting a scrubber failure as part of a comprehensive CO2 monitoring package. That year, Gurr was awarded Eurotek’s Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to technical diving.

Next the soft-spoken tech pioneer turned his engineering prowess on the challenges of recreational diving. The result? His brainchild, the “Explorer,” a unique 32 lbs., electronically controlled semi-closed recreational rebreather” that sells for under $5000 and features a sophisticated resource management system that Gurr first envisioned more than 20 years earlier. San Leandro, California-based Hollis Inc., which purchased the technology from VR Technology, began shipping the unit in 2013.

Gurr subsequently sold his company to UK-based Avon Protection Underwater Systems and went to work for them developing a new state-of-the-art military electronic mixed gas rebreather dubbed the MCM100, which he expects to launch in 2017.

Here in this original 1993 interview, published in aquaCORPS #6, COMPUTING, Gurr, then owner and president of Aquatronics Ltd., discusses his vision for dive computing, which later found its way into the Explorer and some of his other creations. This big-brained man is prolific!

Below is the original interview as it appeared in aquaCORPS Journal #6: “Computing,” June, 1993.

A Whimsical Mr. Gurr at the tek.93 Conference

Gurr presenting at tek.93 with luminaries Dr. RW Bill Hamilton, Sheck Exley and Mary Ellen Eckoff, and Russell Orlowski, Drager USA in attendance.

Reprogramming The Future: An Interview With Kevin Gurr

Menduno: You started designing dive computers some time ago.

Gurr: Six years ago, as more of a feasibility exercise, a couple of friends and I tried to put together a reprogrammable computer. The prevailing attitude of computer manufacturers seemed to be, “Hey, we got a new computer. Throw out your old one and buy the new one.” We wanted to offer divers something more. Mechanically it was not very good, to say the least. So we ended up scrapping the original as soon as it was out and producing an improved version, the ACE ProFile.

Gurr portrait from tek.95

You were able to load different decompression algorithms?

Not just algorithms, but options, functions, upgrades that sort of thing. Then a couple of things happened. A friend of mine had an accident with a high pressure gauge line. The hose exploded and split his hand. We decided there must be a better way to monitor high-pressure air and so we started playing with air sensors. At about the same time, another friend of mine had a really bad spinal hit for no apparent reason. It was a spinal hit following a first dive of the day to 60 FSW for 30 minutes— just one of those unexplained “numbs-you-up” kind of thing. One of the problems he had was that the medical staff didn’t believe his profile when he went for recompression. It gave us the idea that if we could just data log every second of the dive and report exactly what went on—like ascent profile, ascent rate, the whole thing —we could develop better algorithms.

That led to your Quatek enriched air computer?

That’s right. It was essentially a software upgrade to the ACE that offered a gas sensor; an optional on-board analyser, decompression algorithm, and all the data log stuff. You could run virtually any mix you want, change the target PO2s, calculate EADs or ENDs through a window arrangement and four contacts that let you get around the system.

What’s happened?

Basically the company was forced to close its doors due to financing. In some ways, we were our own worst enemy. We were really good with ideas and putting them into preproduction. We had several large companies interested and everyone wanted to buy them but we were never able to get sufficient backing to put them into full production. Ironically we had our nitrox version running nearly a year before the Enriched Air Workshop in 1992. After that nitrox just took off.

In some sense, you had taken the approach of the PC industry; create a standard hardware platform that can run different software packages. Is that the future of dive computers?

I believe there’s a need for it, especially with at least two major navies looking at different approaches to decompression. Today, there’s no real reason why we can’t have a complete electronics system that supports the diver incorporating decompression management, gas sensing, communications, and diver positioning. The technology is here now.

The problem is that the dive computer industry is leagues behind the rest of the electronics industry, as far as that goes, because the mass market is basic air diving. The good news is that air divers are becoming more educated. They’re starting to see communications as viable, they’d like to see exactly where they are on the planet and GPS (global positioning systems) helps them do it on the surface – why can’t it be done below? The answer is it can. It just needs someone to help fund it, to put cash on the line.

Dive computers built by Gurr. Top left: ACE, Top right: ACE Quatek, Mid left VR3 Issue 1, Mid right VR3 issue 2 Bottom left VR2 delta, Bottom right: VRx

Gurr catching some Zs with his Cis-Lunar Labs Mk IV (1994)

What do you think of the new wireless high-pressure systems that have just hit the market?

I think that wireless systems are more of a gimmick than anything in some ways. The important thing is the gas consumption information.

There are a lot of things you could do with that. Depending on the type of dive you’re doing and your configuration, the computer could give you your gas time back in minutes. Or how about look ahead ability; to be able to input the dive that you’re planning to do and have the computer tell you whether you can make it with your reserve intact.

Isn’t one of the problems with a mix computer being able to interface with the computer to tell it, “I’m at my nitrox stop and just switched?” Have you looked at user interfaces?

We have. Mechanically there are ways to do it, but most of them are expensive. We’ve been working on a solution for the last year and have something that I think will work but I’m not going to tell you how we do it. I think the solution is around the corner. It’s not that difficult.

Eventually however, I think user interfaces are going to go to voice synthesis and recognition systems. Not only could the system talk to you, but you should be able to keyword back and say things like, “Switch now”. Technologically, there is no reason why that can happen. It’s being done now in fighter planes and with full facemasks and communications.

That would solve the interface problem. Are you familiar with the “Dive Talker” computer?

A funny story: When it was first out launched at DEMA, I tried it and said to the guy, “It’s a woman’s voice.” And he said, “Yeah, that was my wife.” I said, “I dive to get away from my wife.” He said to me, “Well, I never thought of that.”

Actually, a number of years ago, a scientific institution over here had done a lot of work on voice synthesis, key words, that kind of stuff. They had a really good system and they were looking to license it. At the time, we were going to buy the technology and the ideas, but the market wasn’t great for it. It still isn’t ready for voice synthesis now, not quite.

What is the future for your new company?

New dive computers will live again. Our goal is to develop an integrated diving information system. Whether we get the backing is another matter but it’s the way the technology has to go. Three years ago the timing was wrong. Now all the pieces seem to be falling in place.

Gurr went on to launch the VR3 in 1997