Journal #14

Survivors

Publish Date: Oct. 1995

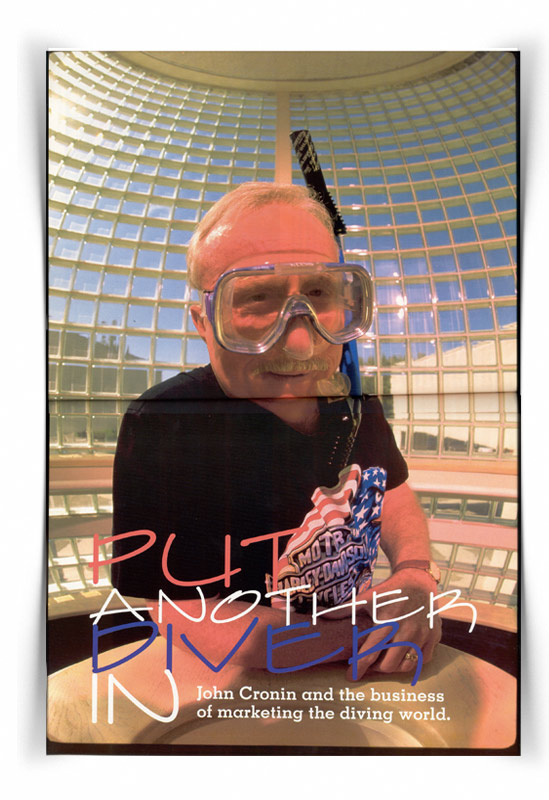

Put Another Diver In:

John Cronin and the business of marketing the diving world

Prologue:

I interviewed the late PADI CEO John Cronin in his office in 1995 just as the training juggernaut was rolling its new Enriched Air Nitrox program. We talked about the founding of PADI, his vision of the diving business, the impact of tech diving on the market, PADI’s new enriched air nitrox courses and his thoughts on tech training and rebreathers and where he believed the market was headed. At the time, PADI’s entry into nitrox was a big deal heralding nitrox’s entry into mainstream diving, and so we ended up making the interview the cover story of aquaCORPS #12 SURVIVORS issue that was published in OCT 1995. Since that time, more than a decade and a half ago, PADI has doubled the number of affiliated stores and resorts and nearly doubled its membership base from 70,000 to over 135,000 members and enriched air nitrox has become the company’s #1 selling specialty course. Here is the original introduction, interview and some of the pictures that ran with it. Mr. Cronin passed away in July 2003. M2.

Put Another Diver In: John Cronin and the business of marketing the diving world

Having sold that first aqualung in 1956, PADI co-founder and chief executive officer John Cronin may well have earned the distinction of being scuba’s most successful traveling salesman. True story. The 67-year-old Irish diving mogul, Harley Fat Boy owner, sustaining member of the National Republican Committee, former Boy Scouts of America director, ex-marine, and angel for a dozen charitable ventures, was reportedly the first person to rack up $1,000,000 in sales in the fledgling US scuba diving industry while teaching scuba to Joes and Bettys on the side. Five years later, Cronin was promoted to the big desk at US Divers—the big blue of sixties’ sport diving—which he manned for more than a decade and a half while concurrently building his privately-held dream, PADI Inc.—the largest dive training company on the planet. A perennial tough guy; it’s fair to say that nobody knows the business of marketing diving like John Cronin. Just look at the house that John built.

Launched in 1966 on big vision, few bucks, a bottle of scotch, and a belly full of frustration with an industry that was turning away potential users instead of training them, Cronin’s PADI has a become a near ubiquitous institution that occupies a unique position in the diving world. Having captured roughly 60-70% of the training market—accounting for over 625,000 diver certifications in 1994; there’s one certified every minute—and representing near 70,000 professional dues-paying members, 2,500 dive centers and 500 resorts world wide, PADI has made diving accessible to the masses on a global scale. A fact that its competitors and vocal detractors are not easily able to forget!

In Europe, PADI is aggressively reshaping the federation system world where the “business of sport diving” is still a dirty word. Reshaping? Its clubby competitors are scrambling to revamp their lengthy not-for-profit training schemes while PADI continues to rack up share with its “Do It Today” motto—American Express welcome here. “Brash promoters flaunting their wares!” one diving exhibition organizer admonished. Meanwhile the “Pee—A—Dee—Eye” is reportedly growing gangbusters in Asia, and has just begun to roll out its spectrum of products in South Africa in hopes of a business to beat the band. The Microsoft of diving? What works works! (As long as they don’t try to reinvent the wheel. Just kidding!)

Long the technology leader, PADI, along with the rest of the blue chip recreational establishment, were caught with their nappies down by the mix revolution and the resulting shifts in the balance of power and underwater cool. As a result, PADI’s claim to fame strategy—diving for the masses, not the classes—appeared to lose currency as new power-player hopefuls—the fledgling tekkie training companies and others—tripped over themselves to woo the classes. But as the Microserfs know, today’s classes become tomorrow’s masses. It all depends upon on your perspective and how you play the game.

Not a company to miss the beat (for long), PADI finally announced their long awaited enriched air program, which will be rolled out at tek.96 conference in San Franciso. Nitrox for the masses? Modular ‘breather courses may not be too far behind. And then there’s the new CD-ROM, the first of a series of new multimedia products, and a crowning Cronin marketing deal to put diving on the desktops of 30,000,000 new Windows 95 users. Fun’s just a click away.

How do you grow a diving business when you’ve already acquired the lion’s share of the market? That’s what we asked John Cronin.

Some people say, “P-A-D-I: Put Another Dollar In.” How do you respond to that?

It was coined by one of our illustrious competitors; I know which one. It’s bullshit because if you look at what we charge our members for our products—and we do this every year and analyze it—we’re a better buy. There’s no doubt that someone who’s a PADI retailer spends more money with PADI than somebody who is with Brand X. The reason is we’ve got a name brand identification of sixty to seventy-five percent—more people come in and ask for PADI certification than any other brand.

The other reason that they spend more with PADI is because we’ve got a good product line. Everything in our product line is the state of the art.

Build what the market buys?

People don’t have to buy our products. If you were a PADI dive center, you might only buy books and never buy another thing. Of course, that would be your mistake; customers are dying for this stuff. That’s why smart guys are buying a lot from us. Because they’re making a piece of profit, a good enough profit that they can run a good operation and offer better services to their customers. That’s what it’s about. It’s business.

Diving is a sport. It’s an industry. And it’s a business. We look at all three. Consumers want to do the sport and have fun, but they want to do it safely, too. If you want to get your cylinder filled, a retailer’s gotta be there, and make at least a reasonable profit. And the instructor has to be paid.

Technical diving is getting a lot of press these days. Do you think it has been good for the over all business of diving?

It’s opened up a new avenue, a new tangent. I don’t think every diver is going to be a technical diver. I believe that one of the biggest challenges in technical diving is educating the public, which PADI is into. The second is also educating the industry and building the addition to the infrastructure so that everyone that wants to participate will have the opportunity.

There has long been a perception that PADI has been against nitrox diving.

We don’t like to jump into things. We want to be sure that PADI belongs there and that it’s responsible to be promoting it.

Being of reasonable size and magnitude in the industry, we research a new technology carefully before we jump into it. So when we do something, our decision is a responsible one—we’re not going to make a knee-jerk reaction before we find out what we’re doing in the market. We want to understand the dynamics of what’s happening and why it’s happening.

What’s happening with nitrox…umm…enriched air?

As far as PADI is concerned, we’re in. We’re thoroughly convinced that it is going to be an important part of our sport, a part of our industry. Hell, a lot of us have been involved in portions of that technology. There’s no magic to it. It was around before WW II. We wanted to understand how the transition was gonna take place, going from air to enriched air. What the infrastructure was going to be? What were the courses? Was it going to be a viable part of our industry?

We researched it, talked to manufacturers, saw where it was going, then did a lot of surveys and stuff before we decided that we were going to enter the field. Once we made that decision, we decided that we would only be comfortable with a program that we had designed from scratch. We’re going to kick it off big-time at tek.96 and DEMA.

A lot of people in the business believe that PADI’s entry will help legitimize the market for alternative breathing gases.

I don’t think that’s a cheap shot at what exists; I think people say that because we have a good reputation and that whatever we come up with will be well thought out, educationally valid, and even more important, that the content of the course will be appropriate from a physiological and technical standpoint.

I’m not going to say anything derogatory about anybody else’s courses, but I think you’ll find when our enriched air courses come out that you’ll be impressed—they’re top-drawer. They’ll address the customer.

How fast do you see the market for enriched air growing?

Slowly at first. The more adventurous divers have already taken to enriched air diving. From here out it will be a promotional and educational process. Within the next five years it could easily be 20-35% of the market.

Like dive computers. Hmm. How about the retailer trying to get set up?

There’s many ways to go about it. We’ve done our research and plan to give them the resources and ways to go about it. That’s our job.

Do you have plans to offer training products in other areas that have been considered technical, like deep diving or rebreathers?

I can tell you that our DSAT (Diving Sciences & Technology Division) division is actively researching what our next role will be in the tech area.

Photo courtesy of PADI Inc.

I’m sure it will turn a few heads when you figure it out. Let me switch gears on you a little. What makes diving so special from a marketing perspective?

It is a unique sport, an opportunity to explore a different environment, a different world. Cousteau coined it—“The Silent World.” It really is, especially the first time in. It defies gravity. You’re flying. It is a special sport, an activity where you can touch the edge of science and adventure. I think we’ve only tapped the surface. You read surveys about how many people would like to try diving. It’s phenomenal.

Most of the people I talk to who’re not divers say, “I’ve always wanted to do that.”

You hit the nail on the head. The way I look at it, we have tremendous opportunities to grow. And it’s incumbent for all of us involved to find ways to introduce more people to diving. The opportunity is there.

Diving is in vogue. Look at TV advertising. Somebody’s selling something and a guy or a guy and a gal are jumping into the water with a snorkel, or they’re going scuba diving. It’s an in-thing to do. We have to make it available to them, make it easy to become a diver. It’s not that difficult; it’s not strenuous. You can go to any level you want. I’m not saying, “Don’t train ’em properly.” I’m saying make it easy, accessible.

Do it today. That s our motto.

Make the technology accessible.

Make it easy.

True story: There was an outfit in New York that sold hiking and climbing equipment. They had a good location, great parking lot, and they moved to a new location—bigger place, better looking store, but they were a block from the parking lot and their business went down. There are guys who walk 17 miles on a Saturday and climb up a goddamn mountain, but they’re not going to walk a block to shop. What does that tell you? It better be easy, it better be accessible.

If we want the industry to grow, we have to make the sport appetizing, easy, accessible, and relatively safe. But it has to be easy to get there. I think the job of all of us in the industry is make diving more accessible.

How effective has DEMA been in that regard?

I think that they’re at a crossroads. They formed a new organization: The Diving Equipment and Marketing Association (DEMA) and if it goes in the right direction, it could do a great deal of good.

Isn’t that supposed to be part of DEMA’s mission—to promote diving to society at large.

If I were writing the charter for that organization, which I’m not, I would tell them to pick out two things to do: one would be promotion, and two would maybe be liability within the industry. Promote diving to new customers and…I just coined it. D-A-R. Diver Acquisition and Retention. That should be the goal. Stop all the other bullshit. Stop worrying about 58 different programs because pretty soon you dilute your efforts.

Our job is to make it easier for more people to dive. Last year, 100,000 people responded to our Discover Diving promotion over a 12-month period. That’s just with PADI. Most of the people weren’t involved with any kind of diving program before. Think about it.

Underwater world here we come. There’s another opportunity—the snorkeling business. It’s part of our market. Our job is to show people that snorkeling is fun and initiate them to the underwater world. We don’t have to convert every snorkeler. The smart guys in the snorkeling business are selling a lot of snorkeling stuff, and now people are used to coming into their stores and dive centers and so are their children. They’re buying snorkels, masks, suits, and travel. They’re not second-class citizens; they’re in a different area of our realm. The dive center people who treat these customers like first-class citizens rather than second-class citizens will be the big winners. This is a big market. Start treating them well.

The retail thing. It all comes together at the retail level. We need to realize that the retailer is the center of the diving industry. They do a pretty good job now, but there’s always room for improvement. Retailers are looking for new and innovative ways to keep their customers. I think the survivors will be the guys with the Marshall Fields or Nordstroms mentality. It’s all about customer service.

When I return my Hertz [rental] car, I don’t have to clean it. It’s their goddamn car. They should clean it up because I don’t care if it’s clean for the next guy or not. Just think about that mentality. Do you clean up your car at Hertz? No. Why do we do it with scuba? It’s archaic to make customers wash their gear. They rented it from you. This kind of thinking will enhance our sport: make it easy, pleasant, accessible. I come out of the retail business and sold to retailers for many years.

When did you start selling scuba?

1954. I was working for a big outfit called Gold Stocks, in Schenectady, selling skis, hunting and fishing equipment. We were Head Ski’s second largest customer and the largest Weatherby rifles dealer, an ultra, ultra rifle—really expensive. In fact, we were the largest weapons dealers on the East Coast and second largest Browning shotgun dealer on the Atlantic seaboard, which was amazing considering we had this small business in Schenectady and Troy; we were really in the ski business.

I was the store manager, and one day a good customer came in and said, “I wanna buy an aqualung,” and I asked, “What the hell’s an aqualung?” He gave me all this bullshit, “It’s great. You dive underwater.” I said, “Why would you want to that?’

He was a good customer, so I started calling around. I called a place called Aqua Gun in Yonkers, run by Ben Holderness, and said, “I wanna buy an aqualung.” [Aqua Gun was bought by US Divers Corporation about two years later.]

He said, “You gotta buy three.”

What in hell am I gonna do with three? So I told him I’d call him back. Then the customer came back in and so I ordered three aqualungs. Later Jerome, the owner, came in and said, “What the hell’s that?”

“An aqualung.”

He says, “What s an aqualung? Who the hell’d buy that?”

“Lennie Jones,” I said.

He knew Lennie Jones. Every week after that, Jerome would come by and ask me, “What’re you gonna do with the other two aqualungs?” A month later he came by and said, “There’s another one gone. Who bought it?“ I told him that I did.

Lennie had talked me into going diving up at Lake George. He was an engineer, had his own compressor and made his own weight belt. I had read the 17 page booklet 14 times and ended up making my own wet suit out of quarter-inch neoprene and cement. It took about six hours. The kit was called an Artico. I think it was $29.95 for the whole thing.

The place was called Bolton Landing. We climbed out of the boat and went down the anchor line to 130 f/40 m. I wasn’t the least bit worried because it was so clear. We went down a sheer wall. It was like riding an elevator. Cold but clear. That was the first time I went diving.

And you kept selling scuba

I eventually got a distributorship from Healthways/Voit in 1956. Voit was buying from US Divers, who were making the valves and stuff. They wouldn’t sell to me direct, but I had Healthways/Voit. I was selling diving equipment wholesale, some ski stuff, and a lot of shooting supplies. I started calling on the dive shops, and a few sporting good stores—it was all just getting started.

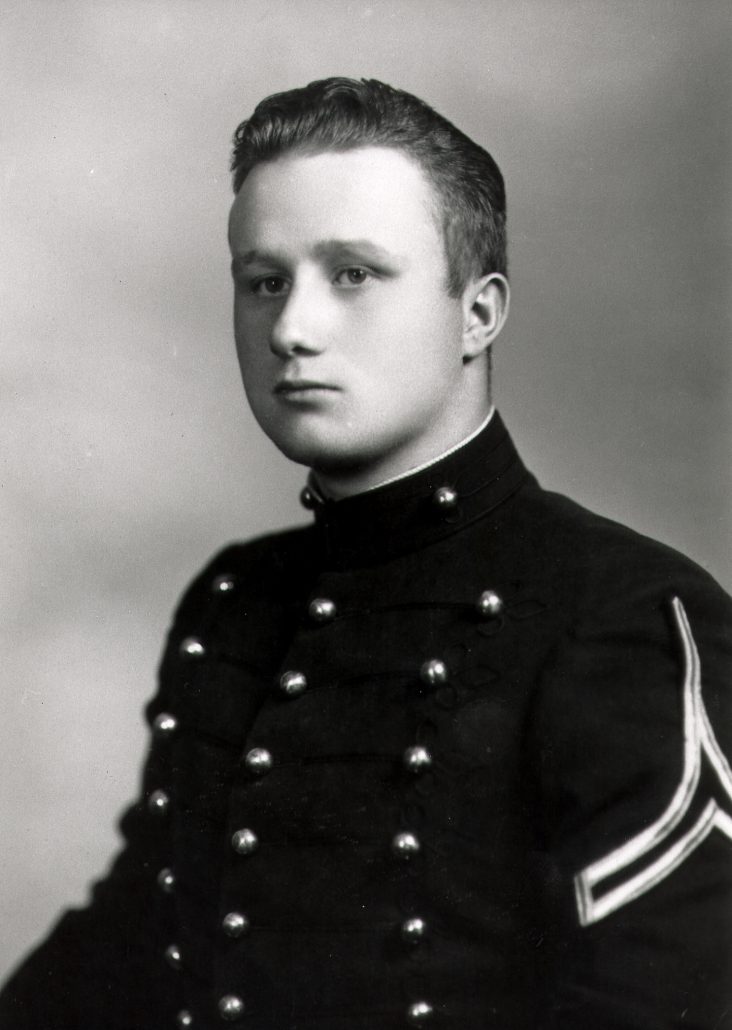

Photo courtesy of PADI Inc.

Is that when you started teaching?

I started diving in ’54, started teaching in ’56. I was putting on free diving classes in one of the big Playboy pools up there. I had eight tanks. We’d get all these people in their bathing suits—it was summertime up there—and let ’em swim up and down once. Fifty, sixty people a night. Unbelievable. Then we’d sign them up for our six-day, six-night course.

Is that when you went to work for US Divers?

US Divers offered me a job as a marketing manager. I moved from Albany to New York City and ran one of the first dive stores, the Aqualung Center, and did a good job for them. I was supposed to promote diving in general, so I was running around talking to distributors, telling them how to sell diving equipment. In the meantime, I rented the Hotel Sutton pool, in Manhattan, Tuesday and Thursday nights and Saturday mornings, and was teaching diving. YMCA was around, but I wasn’t affiliated with them. NAUI was nonexistent in the Northeast. The next year, US Divers asked me to move to Chicago, where I became a regional salesman traveling the Midwest and Canada.

Wasn’t that about the time Cousteau’s first film were being released?

“The Silent World” was released and won an award in 1956. It was

the first shot in arm this business ever had. The second great shot in the arm was the Sea Hunt series with Lloyd Bridges, which got started a couple of years later.

In fact that was about the same time, late ’57, early ’58, I finally got…funny story: The Healthway salesman that I was jobbing for was a guy named Harry Marr, who lived in Boston. He came in one day and said, “I want my spring order.” He did a good job of selling me. Then he said that he might be back in a couple of weeks, so I said, OK. I was always glad to see Harry. We were pretty good friends.

About two weeks later, he came back and asked me if I’d like to buy US Divers direct as a jobber? I used to write to them at least once a month asking them to sell to me. They wouldn’t. I said, “I’d love to, but why the hell would you help me? You’re the Healthways salesman.”

“Not any more,” he said. “I’m your new US Diver salesman, and I’m gonna put you on because I know you can move some merchandise.” By the end of 1959, we were the second largest distributor US Divers had, second only to New England Divers.

.

How long was a scuba course in 1960?

Six lessons. Two checkout dives in one day. That was it. I had a classroom at the Aqualung Center and the Hotel Sutton pool. You had to come to the classroom at a certain time because it wasn’t a modular course. The guy that worked with me, Jim McNamara, was a young guy who just got out of the Marine Corps. He was with the underwater demolition team, and we had a tough time toning him down so that he would realize that we weren’t training these folks from New York to attack Jersey. You have to remember that I was out there trying to raise four kids and pay my rent selling diving equipment. I was frustrated.

The militaristic approach to training?

Ralph Erikson [PADI co-founder] and I talked about it for years. I had met Ralph at a banquet. We went diving a few times. We both felt that these UDT-type courses taught by people with military backgrounds were chasing people out of the sport.

I used to go to the “Y” after I had hit the stores in a town. I remember running into this guy. I knew him. I won’t tell you where because everybody would know who it is. I said, “How are you doing?” He said, “Fine.” Blah-blah-blah. He says, “I run the best course in the Midwest.” I said, “Yeah, how come?” He said, “I had 22 people in my last course and only eight of ’em made it. What’d ya think of that?” I said, “I think you re a horse’s ass. You’re what’s wrong with diving.“ I asked him, “Did you take their money? You took their money to teach ’em, not decide if they were qualified or not qualified. That’s what’s wrong with this goddamn sport.” I walked out on the guy.

The problem.

Ralph Erikson was a swimming coach. He was the guy who really saw the problem with the military. We talked about it all the time. So many people wanted to dive. They’d go to some of these courses, and we’d hear horror stories. They’d lose people the first two nights.

“Can you swim 500 yards?” What the hell do I look like? Tarzan? It was ludicrous. A lot of the criteria was ludicrous. A lot of people had their own criteria.

The YMCA had a course that wasn’t bad. NAUI had a course. It wasn’t a bad course. They used outlines, and the people teaching them were left to their own devices. That was the problem. If the guy was a good teacher, he taught a good course. But then there would be some guy who was trying to prove that he was the only guy in the pool who could do it and that everybody else was a wimp. He really didn’t care how many people he taught or if he taught anyone. That was a major problem in this industry. Ralph and I talked about this for a couple of years.

That’s why you started PADI?

Ralph and I started PADI in 1966 out of frustration.

I heard that it got launched on $20 and a bottle a Scotch.

Fifteen dollars and a bottle of Scotch, and Ralph has yet to pay me for his half of the bottle.

I had just come off the road, and I was so pissed off about this stuff. I called up to Ralph s apartment and he said, “I just got a bottle of Scotch. C’mon up.” I said, “Ralph, it’s time if we’re gonna do it.” We set there that whole night, brainstorming. One of us had a five dollar bill, the other a ten. We threw it in the kitty.

Our first office was my basement. My son Brian [recently appointed a PADI Vice President ] said the only thing he could remember about PADI was I used to say, “Shut up and lick.” He was licking stamps and envelopes. Ralph produced the Undersea Journal. We had it printed at an orphanage in Chicago. I swapped them diving equipment, and got the kids into the pool occasionally. That’s how we got it printed cheap. We really got going in ’67, and I used to come home on weekends and type all the PIC [certification] cards.

That was the birth of the PADI system?

Ralph always said that everybody should be teaching the same thing. I agreed. That’s why I hooked up with him. I believed we had something universal—we didn’t say modular in those days—a course that everybody taught the same way that would be limited to the important things. Cause and effect.

I can remember people teaching not only how to change from Fahrenheit to Centigrade, but how to calculate heat loss in a wet suit, and the difference between 3/16s, 3/8s and 1/4-inch, which is bullshit. I mean, that’s fine if you’ve got a bunch of GE engineers in Schenectady.

Or a bunch of tekkies.

Those were the tech divers. But you take an average guy or gal and tell them, “Before you can really be a good diver, you have to know how to compute your heat loss.” What the hell does that have to do with it? Do they ask you if you can compute the compression in your engine before they let you drive a car. It’s the same thing.

For the masses not the classes.

We wanted to bring diving to the public. We wanted to make it fun, and we wanted the courses to be effective. When the people got out of the courses, they realized, yes, there are certain things that are dangerous. Number two, this is what you can do; this is what you can’t do. Number three, these are the ground rules—the physics and the physiology. And number four, it’s fun. That was our goal, and we took a lot of heat when we started. A lot of people made fun of us. The NAUI and YMCA people called us the Irish Diving Association.

How did you actually create the program?

We designed our first program with about ten, twelve guys. We outlined it in a brainstorming session. Ralph was working on it while I was out developing customers. I was traveling in mid-West and Canada and I talked about PADI and explained where we’re going. We became mid-west based because we didn’t have any money to advertise, so the advertising was Ralph on the phone and John Cronin on the road when I traveled for US Divers. US Divers looked at this with a jaundiced eye.

I’ll bet. It amazes me that they let it go on.

I got called out in 1967 by the president of the company, who wanted to know in plain language, “What the fuck I was doing?” Someone had come to him and raised hell, suggesting that US Divers were gonna be embarrassed, and that this Cronin was competing. I got flown to California for two days and called on the carpet. I said, we’re in the diving business. As far as I’m concerned, nobody is doing the job in education. We talked. I can’t say I made a convert of him, but I did get him to say, “You do it on your own time and don’t embarrass US Divers. US Divers has nothing to do with this, does not condone it, and we’re not endorsing it.” I said, “Fine.”

Because you were their top dog as far as sales went?

That’s right. Then, in 1969, I was offered the job of national sales manager and asked to move to US Diver’s headquarters in Santa Ana, California.

That created a problem at PADI. The problem was that I wasn’t there anymore, and Ralph was only interested in the training and Undersea Journal. People used to call me at my house, and now they were calling him. He called me several times, “I’m sick of this bullshit.” Ralph said, “You gotta do something.”

So, in 1970, I went down to Costa Mesa and rented a big room—about 500 square feet worth—and hired June Nelson; she was our chief cook and bottle-washer. That was the year they made me CEO at US Divers.

PADI grew from one room to two rooms, then three rooms. I asked Nick Icorn, a design draftsman with US Divers who had retired, “Would you like to take a stab at running this for a couple a years?” So he did. He left two or three years later and Sonny Whisenand took over. Then we moved from five rooms and went down to a place on Bear Street in Costa Mesa. There must have been 2,000 square feet down there. We were really cookin’. We just kept growing and growing and growing. Then we moved to Bush Street with 6,000 square feet, and then to 10,000 square feet on Warner. We eventually moved here in 1988, where we have 50,000 square feet.

Photo courtesy of PADI Inc.

You retired from Divers in 1985?

I can’t believe it’s ten years already.

I’d like to know how you managed to run PADI and US Divers at the same time?

It was structured. I always had a goal, and the goal was to improve our courses and increase our market equity, like any business. And I had a propensity for marketing and sales. I always figured the best thing is to have the right product.

And then PADI took off?

We were really starting to be accepted. Everybody woke up in the early- to mid-’70s and said, “This PADI—they’ve got something.” After that, we increased our business 10-20% each year and concentrated on products and programs. By the mid-’80s, we became the largest dive training agency in the world.

Is that what made PADI successful?

Products and programs, that’s what we’re all about. It’s a complex company. Professionally, we have nearly 70,000 members.

I think we have to be one of the four or five largest professional associations in the US—I’m taking a guess. Besides being a professional association, we’re also the largest trade association in the industry—between PADI Retail Association (PRA) with over 2,500 dive centers around the world, and PADI International Resort Association (PIRA). Between the two, we have over 3,000 members. So, we’re a major trade association besides.

What is your model for this?

There isn’t any in this industry. You watch the demographics of the market and ask where is there a need. In ’78, we saw nobody was looking out for the retailers. So we said, there’s a need for that, and we formed the PADI retail Association. We had a lot of resorts that wanted to join, but they didn’t qualify. You looked at the criteria; they couldn’t join. So we thought there was a need, and we formed PIRA. It was a natural. We initiated that about three years ago. We got close to 600 resorts in three years.

Then a few years back, we looked at travel and started the PADI travel network because there was a need for it as a member service. So we opened up a wholesaling agency just for PADI retailers where they can send their members through our membership and they can get a benefit for this and some remuneration.

We’ve made a major commitment to customer service. It permeates everything we do.

How does your recent deal to put PADI on Windows 95 fit into your grand scheme of things?

It’s one facet of a major diver acquisition program to bring new people to diving, to dive centers and resorts, and promote diver education. We hope to reach 30,000,000 computers. It’s the right demographics.

30,000,000 desktops.

It’s a nice kickoff.

They’ll find their way to the PADI home page.

We’ll have PADI dive centers, resorts on there. Again, our goal is to make information on diving accessible.

Is PADI the Microsoft of diving?

I wouldn’t say that; I don’t know.

How would you define the corporate culture at PADI?

You could say we have the lowest turnover rate in the industry, and I know we have one of the lowest turnover rates in the state of California. Because everybody enjoys what they’re doing. Like a family atmosphere, yet everybody gives it their damnedest. We’ve brought in a lot of professionals. I’ve been in the business forty-some years, and I would say there isn’t a better team in the industry than the PADI team. Spiritually, committed, dedication to the sport and where we’re going. It’s family. No politics, no BS; get the job done.

Some of your competitors think that you’re doing too well.

Any time you attain a position up there in an industry, you know you’re gonna have your detractors. But you know what? None of ’em could ever say that we weren’t responsible. Nobody can ever say that we’re dishonest. We tell the truth. Any time we give someone our word, we keep it. People can say Cronin’s a tough son of a bitch, but in the same breath they’re going to say, he’s an honest son of a bitch. That means something to me.