Journal #10

Imaging

Publish Date: June 1995

PUSHËN D’ART:

INTERVIEW WITH HOWARD HALL

Here is the original interview as it appeared in aquaCORPS, # 10 IMAGING, June 1995.

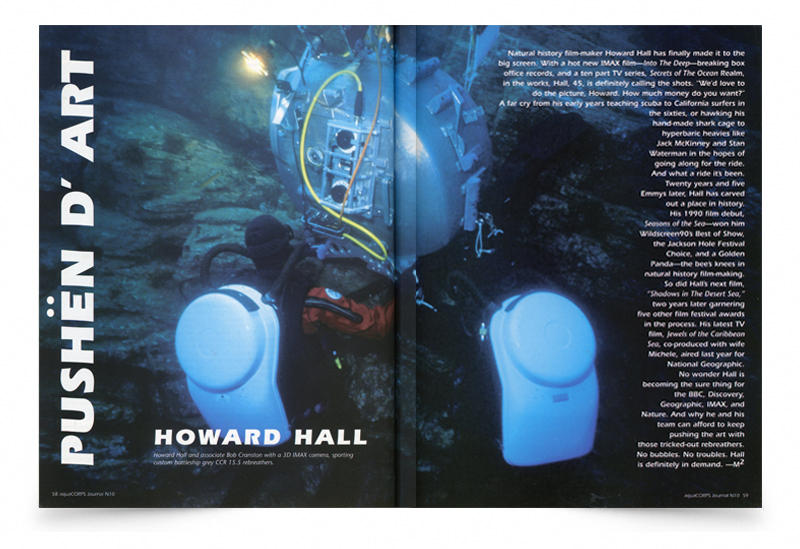

Natural history filmmaker Howard Hall has finally made it to the big screen. With a hot new IMAX film, “Into The Deep,” breaking box office records, and a ten part TV series, “Secrets of The Ocean Realm,” in the works, Hall, 45-years old, is definitely calling the shots. “We’d love to do the picture, Howard. How much money do you want?”

A far cry from his early years teaching scuba to California surfers in the sixties, or hawking his hand-made shark cages to hyperbaric heavies like Jack McKinney and Stan Waterman in the hopes of going along for the ride. And what a ride it’s been. Twenty years and five Emmys later, Hall has carved out a place in history. His 1990 film debut, “Seasons of the Sea,” won him Wildscreen90s Best of Show, the Jackson Hole Festival Choice, and a Golden Panda—the bee’s knees in natural history film-making. So did Hall’s next film, “Shadows in The Desert Sea,” two years later garnering five other film festival awards in the process. His latest TV film, “Jewels of the Caribbean Sea,” co-produced with wife Michele, aired last year for National Geographic. No wonder Hall is becoming the sure thing for the BBC, Discovery, Geographic, IMAX, and Nature. And why he and his team can afford to keep pushing the art with those tricked-out rebreathers. No bubbles. No troubles. Hall is definitely in demand.—M2

PUSHËN D’ART: INTERVIEW WITH HOWARD HALL

You recently were quoted as saying that the business of making underwater films was better than its ever been. Would you elaborate on that?

Hall: In 1976, you could have looked in TV Guide and not found a single documentary that was made in the United States with the exception of maybe “American Sportsman” or “Wildlife Kingdom” if you want to call them documentaries. There was no market in the United States for wildlife filmmaking; no place you could sell it. If you wanted to be a wildlife filmmaker, you had to work for the BBC, which were producing big budget films and doing an extremely good job of it. NBCs Survival Special was being shown about four times a year, and Nature was still running. Both were bought from the English. That’s all changed now. Most of the premiere wildlife film-making is being made now in America by organizations like National Geographic, ABC/CAP Cities, Discovery channel, which has 24 hours a day of wildlife and adventure stuff. Discovery is an enormous market considering how much documentary material they have to eat up all the time, and it’s a growing business. There’s going to be a natural history network coming online soon. And in addition to that, home video markets have been exploding. The market is enormous. Plus, the industry has figured out that the way to make these films is to do co-productions, so that the British and Americans get together and do a production with the Japanese and Germans.

What does that mean for people trying to get into film-making?

Even though there are tons of markets, it’s the same Catch-22: somebody trying to break into the field is going to find it almost terminally frustrating because nobody’s going to give them the money to go out and shoot a film until they’ve demonstrated that they can do it. That first major hurdle is almost Olympic class, one of the biggest Catch-22s there is. Breaking into that business is extremely hard.

It’s completely understandable when you consider that a documentary film, an hour film, gets produced for anywhere from $250,000 to $750,000 or more. Nobody’s going to hand you half a million dollars to produce a film unless they feel like they can trust you with the money; that’s a lot of money to anybody. The people that pay for these films tend to give the money only to people who have proven competence in being able to manage a budget in the past. Just because you can shoot film, or direct it, doesn’t mean you can run a budget. In the filmmaking business, it’s extremely commonplace for producers to go over budget, go over schedule and make essentially a financial shambles of the business.

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

So what do you do?

It’s a matter of networking more than anything else. You have to get into the business any way you can, whether it’s as a cameraman, as an editor, as a line producer, and be visible for a long period of time. Once you’ve been around for a long enough period of time, people feel like you’re not going to become flaky if you were given a ton of money. It’s a matter of being around and being persistent. That’s the other part of that Catch-22; most of the film deals are done on a very personal basis. Getting to know people becomes really important when you’re getting ready to take a whole bunch of their money.

Who did you get to know?

I’d done assignment work for years, many years, and wanted to produce a film on my own. I ended up writing a letter to a fellow who produces NET’s nature series, and my timing was good. I already had a good reputation as a cameraman, and he just decided to take a chance. It was a very /ow-budget film at the time, but it was extremely successful. “Seasons in the Sea” aired in I 990 and won a lot of awards. Because of the success of the film, my next contract was extremely easy. It’s back to that Catch-22; I had two things going for me. One is that I had made a film and demonstrated I could run a budget and stay on schedule, so I could be trusted with the money; that’s the most important thing. The second thing is I made a film that was at the time recognized as the best wildlife film of any kind made in the world. It won two major awards: the Golden Panda Award at the Wild Screen Film Festival in England and a similar award at the Jackson Hole International Wildlife Festival. Best of Show in both places. After that it became a lot easier. I could get a contract with almost any broadcaster just by calling them up and saying, “I have an idea; what do you think?” The next film I did, basically I did over a cup of coffee. I said, “I want to do a film on the Sea of Cortez, will you bank me?” The guy says, “How much do you need?”

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

What makes an underwater wildlife film good?

Everybody’s got their own style. My films are very strong on short animal behavioral sequences, with lots of diversity, though they tend to be weak on general story. I know that’s a weakness. My films have no major story that goes from one end of the film to the other, but they are very strong on short stories, almost like a magazine-format film. In the case of Seasons, there were 20 or 25 short stories of different animals doing different things. The behavioral sequences were very strong; many of them were things that nobody’s ever seen before. That’s what made the film successful.

That’s the hot button in wildlife- to shoot new behaviors?

Two things work really well in animal behavior sequences: one is some kind of anthropomorphic quality that makes people feel like they can identity with the sequence. I’ve always been pretty strong with that. The other thing that’s important for wildlife sequences is showing behaviors in a way that hasn’t been seen before, or simply behaviors that have never been recorded before. In “Seasons in the Sea” we had a half-dozen animal behavior sequences that nobody’s ever seen. Most of the films that I’ve done since then have always had something that nobody’s ever seen.

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

You’re a filmmaker. But what do you actually do?

That’s a good question because people assume that I just go out on a boat with my movie camera, dive and film animals. That’s how I take my vacations! The fact is that being in the field on a boat filming animals is the fun part of the job. I spend maybe an average of about a hundred days a year in the water filming. The rest of the time I spend in scripting, organization, budget analysis, and handling correspondence.

This week, I just completed the scripting for a series of ten half-hour wildlife behavior films I’m going to do. It amounts to about 150 pages of script and took me three months to do. That’s just pure boring work. Each budget for one of these films has 800 line items; the budgets are very complicated and require constant maintenance. It’s a lot of hard work. Once the scripts are done, you make a list from it and shoot what’s on the list. That’s easy. The problem with making films is you start with a certain amount of money, say, a half a million dollars to do an hour film in two years. That’s a typical production schedule for a major documentary. The idea is to finish two years later with no money and the film done. That’s surprisingly difficult to do, so you have to plan where every dime is going to go, and you have to reevaluate that plan every step of the way.

Did you face the same Catch-22 on your first IMAX production “Into the Deep?”

I didn’t face the same Catch-22; they came to me. If I’d gone to them, I wouldn’t have had a chance. One of the founders of IMAX came to me and had a contract to do an underwater 3-D film, and he was looking for somebody to do it. He had seen my television films and thought I offered a chance to do something different. I didn’t take him seriously for a considerable period of time, frankly, because the whole idea seemed crazy. So I really didn’t have to work very hard to get the contract; it just kind of fell in my lap.

I understand it was one of the best grossing films in the U.S. last Thanksgiving weekend?

It was the single highest grossing screen in the nation during Thanksgiving weekend, which probably meant in the world. That’s a big deal for me, and a big deal for IMAX. More importantly, it’s a big deal for the documentary community because it means that documentaries can make money in a theatrical format. That’s real exciting.

Because the mindset is that documentaries don’t make a lot of money compared to entertainment films?

The conventional wisdom is that nobody will come see them. They won’t make any money. And the theater will go empty. The reason SONY ended up showing “Into the Deep” in their new Broadway, New York theater is because the film they were making to show on opening day wasn’t finished on time. All of a sudden, they were without a film. The irony was, we went to SONY when we first made the film, and said, “Would you like to contribute toward the budget of this thing for a lease-option on it?” They just laughed at us and said,

“No. We’re not that kind of a theater. We’re doing entertainment films. We’re not interested in documentaries. We don’t want anything to do with your film.”

Then, a year and a half later, their film isn’t finished and they came to us, kind of sheepishly, “Let us look at it.” They looked at it and said, “Well, we have no choice. We have to show something on opening day.” So they put in my film and another film called “The Last Buffalo, 11 which was sort of an art/natural history film. “Into the Deep “just killed them. It’s been sold out almost ever since.

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Cool. Is IMAX becoming an important format for making underwater films?

There’s no question that IMAX is an up and coming format for doing wildlife films of all kinds.

Is it a lot more expensive format to work in?

There’s no question about it. The size of the gear and the cost of shooting is a major issue when you move up to larger formats. Television becomes extremely easy. When you go from video to 16mm film, you go up one level of cost when it comes to shooting. Then when you go from 16 to 35mm, it’s another level. IMAX 3-D, that’s as complicated as it can possibly get. It’s much harder to make a film in IMAX than in television, and the cost and complexity of getting a 1500 lb. camera to a particular site are greatly magnified.

Do you see yourself doing more?

There’s a very good chance that I’ll be doing 80% IMAX work from here on out. But I don’t know that. I’m busy doing this TV series now and the next project could very well be an IMAX project. If it isn’t, I may be back in television for an extended period. I kind of like the idea of working in IMAX because I think the films can be more sophisticated in a lot of ways than a television film can be, and they’re seen over a longer period of time whereas television films get aired and then that’s the end of it.

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Whats in store for Howard Hall over the next l 8 months?

The TV series called “Secrets of the Ocean Realm,” 10 half-hour shows shot all over the world. We’re going to put in about 130 days of diving over the next 18 months. I’m not sure where it will air yet; very likely on Discovery or National Geographic, but I don’t know. It’s being made for a distributor.

I’d like to talk a little about your diving operations. How much planning goes into your shoots?

That varies a lot. A lot of the work we do is in 25 feet of water with no planning, no nothing. We just put on a scuba tank and come up when we run out of air; as simple as that. Alternatively, we’ll be working on a North Carolina wreck in 140 feet of water this May, with rebreathers and oxygen decompression and the level of complexity will be much greater.

Do you generally use a support diving team for something like that?

That varies with the gear and so forth. Typically I go down with one main assistant and sometimes two main assistants, depending on what kind of gear we’re using. There’s usually a lot of planning involved in relationship to the animals and how we’re going to approach them and what gear we’re going to use and that sort of thing As part of that is the amount of time we can stay at a depth, how much decompression is involved and how many dives you can make during a day or over a week-it all comes into the planning of whether you can get a sequence at a particular depth or much greater.

In the case of this work in North Carolina, we don’t expect to get much more than a particular species of shark swimming around and interacting with the fish that tend to school with it. I wouldn’t expect to get mating behavior or the animal giving birth. The amount of time you’d have to spend down at 140f/43 m to capture that behavior would just make it impossible. That’s the kind of planning you end up looking at.

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Let me read you a quote from your article in the January/February issue of Ocean Realm. ‘”If you’re not fascinated by the technology incorporated in a mixed gas rebreather, and are not attracted to the prospect of solving technical problems underwater, then rebreathers are not for you.” How important of a tool have rebreathers been for you in your work?

The rebreather has been an important tool, but for surprisingly different reasons than I had expected. The main reason we got into rebreathers was to avoid the bubbles, so we could get down and photograph animals that would normally be disturbed by bubbles. That worked especially well with hammerhead sharks and garden eels, but it has not produced an amazing effect with all the other animals. Most of the things that I’ve been able to do, I could have done with scuba. That surprised me. I would have thought that we’d see things that nobody’s ever seen before just by virtue of..

…. the aquatic stealth thing?

Exactly. On the other side of the coin, the amount or additional bottom time and the minimal decompression has proven to be a major big deal. A lot of our work is done between 50f/15m and 70 f/21 m. The amount of time you could stay is really limited with air and open circuit. With the rebreather we’re able to stay essentially as long as we want and that’s produced a dramatic effect in the kind of sequences we’re able to get on film. That’s been the most important thing.

You and Bob Cranston are probably in the top five civilian divers in the country as far as hours on a rebreather-very few people have access to them. How reliable are they?

There’s two kinds of failures we’ve had; straight mechanical failures, where things broke, and failures where we’ve just plain screwed up. We’ve actually gone to the trouble of allowing almost all the systems in our rebreathers to fail on purpose so we could learn what that experience would be like. We’ve had everything fail, although we haven’t flooded the canister. We’ve had sensors fail, the scrubber fail, had oxygen levels fail, we’ve had batteries quit on us, you name it. We dive the system assuming that all those things could go down at any time.

Given that, are you more comfortable on the rebreather or less?

I’m as comfortable on a rebreather as I am on scuba, in many ways. more comfortable. I don’t have to worry about running out of air. I don’t have to worry about decompression problems when I come up from the kind of diving we typically do. In some ways, it’s a lot safer.

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

Photo courtesy of Howard Hall

It also sounds more demanding at the same time. More diligence and discipline than diving open-circuit scuba.

There’s no question that the amount of gear you have to take with you, the maintenance of the gear, and the mental planning you have to go through every time you dive a rebreather, is much more-the “What am I going to do if?” That’s all pretty simple with scuba. The other thing about rebreathers that people haven’t really considered is that there are a lot more stupid things that you can do with a rebreather. People reading this are going to say, “Well. I’m not going to do anything stupid with rebreathers because I know they’re dangerous; I’m going to be careful.” But you gotta ask those people. “Have you ever jumped in the water without your fins on?” I’ve done it numerous times.

I have too. “Something’s wrong here; what doesn’t feel right.'” Then you realize, ‘”Oops, I didn’t put my fins on.”

Right. With a rebreather, that’s going to mean you forgot to turn on your oxygen or diluent, or plug your battery in or not replace it in time, or forgot to replace your scrubber when you should have. It means you didn’t turn the unit on. Both Bob and I have done a lot of those things. You need to assume that kind of things going to happen. and have a diving protocol that you go through that’s going to catch that mistake.