Journal #16

O2N2

Publish Date: Jan. 1996

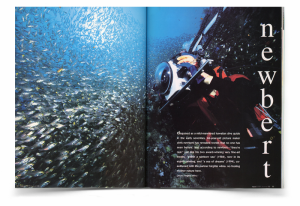

NEWBERT

Disguised as a mild-mannered Hawaiian dive guide in the early seventies, 46-year-old picture maker Chris Newbert has revealed worlds that no one has seen before. and, according to Newbert, “they’re real.” Just like his two award-winning very fine-art coffee table books: “Within a Rainbowed Sea” (1984), now in its eighth printing, and “In a Sea Of Dreams” (1994), co-authored with life partner Birgitte Wilms. No fooling mother nature here.

Newbert

What makes your images so off-world?

Style is part of it. So much of underwater photography today is people imitating other people. There are not very many unique voices out there. So much is underwater photojournalism, which again does not feature the marine life so much as the sport. But I think that gets very old. You’ve seen one diver holding a pufferfish, you’ve seen them all. I’ve tried to explore the aesthetic qualities of the subject matter, and have tried to find unique perspectives.

That no one had seen before?

I think I’ve created something different—I’m not saying it’s better or worse. In the world of underwater photography, it’s distinctive, so I think that’s attracted attention. I like to think that I place a high value on the technical qualities of the work, so I think there are elements in it that have made it appealing to a broad spectrum of the public—not just the diving world.

There’s a look that some of your images have, as if the fishes—the life on the reef—were just frozen in space-time. You don’t see that in other people’s work. How do you describe that?

I like to portray that cornucopia of life found on the reefs, so I like to get as much life into the picture as possible. Technique-wise, for the big reef shots, I think what I do well is the lighting. The technique involves manual strobe photography with differential lighting ratios and the use of diffusers and various other techniques to balance lighting across a wide swath of reef, particularly where the subject matter may be at different distances from the camera. It’s not something someone’s going to be able to do when they set everything on TTL and just drop it down in the water and start poking the camera here and there and pressing the shutter. It requires a studied approach to photography.

Different from the surface?

There’s very little that differentiates underwater photography from land photography. The reason why most people aren’t better underwater photographers is because they’re severely lacking in their fundamental knowledge of photography. They never bother to practice. They’re so obsessed with taking great photographs, they never become good photographers. They never take that step-by-step learning process that any skill requires.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

Is it a matter of shooting a lot of pictures?

Thousands, and ignoring the subjects. A lot of people will never press the shutter release unless they’re faced with an interesting subject. I’ve maintained they will become a better photographer if they go down and shoot rocks, just rocks—or anything. You don’t need a great subject. The most famous picture by Edward Weston—who’s probably my photographic hero—is of bell peppers on his kitchen table. Most people would overlook bell peppers, but he was such a master of photographic technique that his bell pepper photographs transcended the subject matter and became sensual works of art.

It’s not enough just to find a subject; you have to think the photographic process through, from lighting angles, to shadow-ratios, to points of focus, etc. My whole approach to photography is that of making photographs rather than taking photographs.

Talk to me about how you make those ultra-macros.

If you look in Within a Rainbowed Sea, there’s the genesis of those images, way back fifteen years ago—the parrotfish eyes, the octopus eyes, and things of that nature. I think my technique evolved with it. In the new book, In a Sea of Dreams, these pictures employ a very, very flat lighting technique and that enhances the graphic nature of the picture. Flat lighting, equal lighting ratio, shadowless lighting. That means that the two strobes utilized are of equal power, equal distance so that there is no shadow produced in the photograph. That one’s a very flat, graphic look to the picture. If you were to introduce shadows into those off the sides of the gills, you’d have a very different look. I’m not saying it would be better or worse; it would just look very different. I think the kind of look that those have, that people have trouble trying to articulate what it is they’re seeing, I think in large part revolves around that lighting technique.

What role does your equipment play?

Technique is, of course, the ultimate in importance, but you still need the equipment that will allow you to do it.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

Are you a gearhead?

The opposite. I’m far less equipment-intensive than my colleagues. I’m still using the same basic stuff: Canon F-1 cameras and Ikelite housings for close-ups, which a lot of professionals and serious amateurs laugh at. I think they’re the superior for close-up photography. People tend to think that if you spend enough money on equipment, you’ll have pictures that will reflect the price of the camera. The two don’t equate necessarily.

Unfortunately, so much of the equipment available—past, present and probably future—is designed by engineers, not underwater photographers. It has a great potential of being more of an encumbrance than a creative tool. Though any good camera can take a good picture, the way some of this stuff is designed, engineered and produced makes it difficult for the photographer to capture that image the way they want.

The opposite. I’m far less equipment-intensive than my colleagues. I’m still using the same basic stuff: Canon F-1 cameras and Ikelite housings for close-ups, which a lot of professionals and serious amateurs laugh at. I think they’re the superior for close-up photography. People tend to think that if you spend enough money on equipment, you’ll have pictures that will reflect the price of the camera. The two don’t equate necessarily.

Unfortunately, so much of the equipment available—past, present and probably future—is designed by engineers, not underwater photographers. It has a great potential of being more of an encumbrance than a creative tool. Though any good camera can take a good picture, the way some of this stuff is designed, engineered and produced makes it difficult for the photographer to capture that image the way they want.

I’m not presently doing any darkroom work. I used to do a lot of it. But we moved from Hawaii to Colorado a couple of years ago, and although we built a big darkroom into the new house, I still haven’t had time to set it up because we’ve been chasing our tail with a million other projects. Doing my own darkroom color printing was a very, very vital part of my evolution as a photographer because when you make your own prints of your work, all of your shortcomings and all of your technical errors on the original photograph are magnified when projected on the easel.

You told me at the tekConference that we were at the dawn of the era of the big yawn in photography. What did you mean?d

I think we’re witnessing the beginning of the death of photography as a meaningful medium. We’re still at the embryonic stages of digital imaging, but imagine a few years hence, the technique will be so refined that even a trained eye won’t be able to determine that all the elements were scanned in. Be that as it may, the picture will look spectacular.

Once this becomes commonplace, advertisers and editors will be keep upping the ante of the threshold of excitement on photographs until eventually nobody will give a damn because it’s not real to begin with. If two manta rays are good, let’s put in six, let’s put eight manta rays in this shot—hey, why not a couple of hammerheads. The sky will be the limit. That final image never existed in reality, and the public will just plain get bored with the whole thing. Legitimate, honest photography will be so far down on the dazzle scale that it will fail to excite the public at all.

You’re saying that fiction will be more exciting then what we’re calling reality?

What magazine editor or art director for a commercial product is not going to succumb to the siren call of digitization when they know they can make a more commercially viable product? Eventually, we’ll have every conceivable photographic element on CD-ROMs somewhere. What will the role of the professional photographer be at that point? There won’t be one. Rather than paying a professional to go out and take the shot, someone will patch together whatever they need, make whatever spectacular image they’re looking for.

Is it real or digerati? Is it enough to divulge that the image has been created on the computer?

Disclosure is only one important element of it, but it doesn’t solve the era of the yawn, because who cares? It’ll be like the MTV world in stills. After you see so much of it, it’s like enough already.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

I wonder if people said the same thing about painting when cameras were introduced?

It’s absolutely not the same. What they [the digerati] are doing is creating images that, for all intents and purposes, identically replicate a photograph. A photograph never replicated a painting. Those two never competed with each other; they serve different purposes, although eventually they could both be collectible art. But the whole point of digitization is to make it look like an original photograph. That is the problem. I’ve seen ads from a company that will take family photographs and remove the divorced spouse, add somebody new in, and end up with pictures that look real. Look at where this thing is going. We now have family photos that represent the true history of our family as it existed at a specific date in time. This won’t happen any more. This whole essence of photography, which is truth, honesty, has been lost; it’s been taken away.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

What is the market today for fine art underwater photography?

It’s a limited market. I got my start doing gallery shows, which was very fortunate in terms of the evolution of my career. If I started with editorial work for dive magazines, it would have led me to a style of photography featuring divers in action and that whole genre—the underwater model with the matching makeup and all this gibberish. Instead, I was photographing subject matter based on the aesthetic qualities of the marine life with the goal of turning out prints which I would then display in galleries and private showings. So it very much suggested a certain type of approach to photography that was very important in my eventual publishing career doing books like “Within a Rainbowed Sea” and “In a Sea of Dreams,” which I consider photographic art books rather than diving books.

Aimed at a broader audience?

You’ve got to take pictures that transcend the subject matter. Of course, fine art color photography always had a disadvantage insofar as color photography is a very volatile medium that previously did not have any archival final form. As a result, everything had to be priced more as decorative art than fine art. There’s always been a separation between color photography and black-and-white fine art photography.

When you say archival, do you mean that the film would degenerate over time?

Right. Not only the original film, but any print form previously known—with one exception—would deteriorate with age. The color would shift and eventually fade away, as opposed to black-and-white photography, which can be made, for all intents and purposes, archival and permanent. The one form of color printing that is truly archival—tricolor Carboro printing—was heretofore so exorbitantly expensive, that just to have the prints made was not an option. It’s made from layers of pigment generated from the color separations which are laid down just like oil paint on the chosen substrate—acid-free paper or whatever. It was an archival form of print generated from an original photograph. Now these processes have been updated and modernized so that Carboro prints, which now go under the name of Evercolor, are much more affordable than they were.

How about storing the image digitally on CD-Rom?

That’s not a form that would be collectible in the fine arts world. It’s got to be made in a presentable print form that can be shown to a buyer who will want to purchase it for their own private gallery or decorative scheme.

Your books have such extreme quality. Do you use a special printing process?

It’s not so much a special process; it really comes down to a tremendous financial commitment by “Ocean Realm” [magazine] to reproduce the images with the very finest of papers, the very finest of color separations, and the most expensive inks. The original scans are ultra-high-density scans, like one gigabyte per image, which are then greatly reduced for the final image. The color separations for the new book [“In a Sea of Dreams” ] were done by the same company that did the color separations for Within a Rainbowed Sea. They’re more artists than they are technicians. Many things have to be redone over and over and over in order to try to approximate, as closely as possible, the original.

We printed both books in the United States with Dynagraphics in Portland, Oregon. Wy’east Color in Portland and Seattle did the color separations. You pay a lot more to work in the United States; you might spend 30% more to get that extra 10% of quality. You have to have the commitment to spend the money necessary to get it done right.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

You have created a lifestyle around your work. You have your books, photographic tours. What’s a day in the life of Chris Newbert like?

“Deda” [Birgitte Wilms] and I don’t have set routines because we’re involved in book publishing. We have a stock photography business, and we have our tours. Those are the three key elements in our lifestyle, and what we do on a day-to-day basis is dependent on what’s most pressing. We also answer a lot of requests for photographs from various publications around the world; that always takes a big chunk of time.

What role does Birgitte play in your work?

Birgitte and I met eight years ago and have been married for six years. Probably five to six years ago, she started dabbling in photography. Now she’s a full-fledged partner, and I respect her work tremendously. Her role is primarily photographic. I think the new book is far superior for having her work in it.

She’s a Danish citizen, so English is her second language, so she doesn’t participate so much in the writing of the books or any articles we might do. Although she does function as a critic, reading it through and expressing her likes and dislikes.

How much time do you spend in the water?

We average ten trips a year—long duration, two-to-three week trips—so we’re traveling six months out of the year, either directly or peripherally related to the tours. The rest of the time, we stay home and do the tremendous amount of administration that goes into running the trips. We are fortunate in that we only run trips where we want to go; to the areas that we feel represent the best diving in the world or the most exciting photography. We don’t run trips just because we can make money on it.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

Let’s talk tech.

I tend to dive deep and long, but I’m doing it with standard [recreational—ed] equipment. I do a lot of decompression diving; sometimes several dives in a day. I do tremendously long shallow-water stops. Over thirty years of diving, I’ve never been bent.

Naturally, I’m keeping a keen eye on the evolution of consumer rebreathers, which I think will be a tremendous asset to photographers. The total silence is magnificent.

Have you spoken with Howard Hall or other photographers who are using rebreathers?

I haven’t spent time with Howard, who’s the only one I know who’s used them extensively. I’ve spent some time talking with Bob Hollis [Oceanic founder & CEO—ed.] about his unit, which I’m very excited about. When I’m working close to a lot of marine life, every time you exhale, it scares them. I just have to believe that rebreathers are going to be a tremendous asset.

Mix?

I haven’t explored nitrox; I’m not comfortable with the depth limits on it because very often I find myself having to go deeper. But I sure do admire the extended bottom time. I think that as nitrox mixes start to become available on dive boats, I will be very interested in it. Nearly everything I’m doing is on live-aboard dive boats.

Do you always carry your camera?

Always. I don’t always shoot, but I will hardly ever dive without it. But I go many dives and don’t take a single picture, or don’t even feel compelled to. A lot of the time I don’t get any photography done because I’m busy diving, exploring the reef. I always want to see what’s up ahead, particularly when we’re diving new and virgin areas that no one’s ever been on before. I get a tremendous satisfaction out of going 100 yards farther off the reef and seeing what’s out there, knowing that no one else has ever seen it.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

Newbert Off Line

aquaCORPS #2 SOLO June 1990

Photographer Chris Newbert has become somewhat of a legend in underwater photography circles. His distinctive camera work has graced the pages of National Geographic Magazine and many other publications, including his book “Within a Rainbowed Sea.”

aquaCorps (AC): There’s this rumor floating around the industry about you hanging at 200 feet/ or so alone in the middle of the night with a big light shining down, waiting to photograph creatures that come up from the depths. What’s the story?

Chris Newbert (CN): It’s an absolutely false rumor. The truth is, it was a very small light. Actually, the basic facts as outlined are quite true. I was doing some open ocean drift diving, going out maybe eight to ten miles from shore into water about 5,000-10,000 feet deep. I would stop my boat and descend to 200 feet to shoot and then gradually work my way back to the surface. I would go as deep as that and basically drift in the open ocean with the boat unattended just above my head.

At night, the deep sea scattering layer would migrate vertically towards the surface. I would only dive on dark, moonless nights, because only on the darkest of nights would the creatures come close enough to the surface to photograph. By “close enough,” I’m talking about the first 200-foot layer. Whereas on a bright night with a full moon, the animals might only come up to 300-400 feet deep.

Photo courtesy of Chris Newbert

Were you on a line?

No, actually I wasn’t.

What were you shooting? Large pelagics? Sharks?

There’s no point in trying to film large pelagics out there. You can see them during the day under much more favorable photo conditions. I was looking for things that were unique to that environment and time of day-the migration of animals in the deep scattering layer that occurs only at night. Generally these were small things: larval forms of life; little fish, pelagic octopi or seahorses; or flying fish at night.

Why solo?

Well, you have better interaction with animals when you’re alone than when you’re with another person. My feeling is you’re always going to have better animal activity, more intimate contact with aquatic life. I would also say, I dive alone because I’m a photographer. All photographers have to admit, if they’re honest, that they dive alone. That is, they don’t perform their half of the bargain in the buddy system. You’re not paying attention to your buddy; you’re paying attention to your photography.

Do you ever feel afraid working like that?

The scariest part is when you’re still on the boat and you’re thinking about going in, and the lights on the shore are 10 miles away and the water looks dark and cold. But once you’re in the water, it doesn’t feel that different from any night dive. You have no sense of depth, really. You’re surrounded by black so you can’t tell that it’s 10,000 feet to the bottom or 100 feet to the top; 10 miles to the shore or 10,000 miles to Japan. You’re just in a black void and your perception extends only as far your underwater light.

God knows what’s lurking over your shoulder. You could turn your head around and you wouldn’t see it. All you can see is what’s in that beam of light. So it was actually fairly tame. I suppose if I was out there and something huge showed up that started chasing me around I’d be damn afraid. But the concentration required by photography, to a large extent, keeps your mind from wandering. So much of your attention is drawn toward all the things around you. You just put the fear out of your mind, and that’s easily done by your fascination with the more important things—the real things. Not abstract fears, but the concrete things.

The deep scattering layer is a layer of phytoplankton that migrates in depth in response to changes in light intensity, inducing the creatures that feed on it to migrate as well.